Recently I got the chance to talk to Mick Gordon, who is one of Australia’s most notable video game composer. The interview started off with Mick asking where I’m from, which led to the discovery that the soundtracks for games such as Wolfenstein II, Killer Instinct: season 2, Doom and Prey were done in Ballerat. We quickly moved on to talking about his entry into the gaming industry, the Game Masters Exhibition in Canberra, Doom Eternal and so much more.

So you’re in Canberra for the Game Masters exhibition as a local hero, it must be validating to be held in such high regard and stand as a representative for talent coming out of the Australian games industry?

Whoa! I wouldn’t say it’s anything like that, it’s obviously a great privilege and an honour that we’d be even considered for such a thing. The part the excites me the most, honestly, is that here in Australia we are isolated. And as much as modern technology has changed that and alleviated that, we are isolated. There is such a wonderful history of video games here and there are so many wonderful people in Australia doing all sorts of incredible things.

I mean, if you’ve played games in the last few years, I can guarantee there’s at least one that was made in Australia. If you read about a game in the news, whether it was Hollow Knight or Fruit Ninja, there’s so much great talent. Why they’d pick me to go to this thing, I don’t know. I have no idea. But for Canberra to put this thing on, for the NFSA to bring this exhibition here, that’s incredible.

And when they reached out and said: ‘Hey, do you want to come and do a panel and have a chat about some things?” Of course, I’m more than happy to do that. When I started in video games, there were about forty companies in Australia making games and this is before GFC. And even then, they were very secretive. And the game industry is, I think, way too secretive, I’m very much working to change that. I think we could benefit from not being so secretive. Putting visibility on the Australian game industry is always very, very important, I think.

A great privilege and an honour to be here, for sure.

Do you think the government could do more by way of funding for video games in Australia?

Oh, I don’t play that line at all, I deal with Americans who would laugh at the notion of the government even funding anything. I think there’s so much talent here and if you want to get into games, you’ll find a way to do it. I think in this day and age it’s easier now than ever to make a game.

I think that conversation comes about because we see a lot of government money that could maybe be considered misappropriated for certain things that you think it shouldn’t go to. And then you think well if you’re giving money to that helicopter ride or that dickhead politician, you start feeling that that could really benefit if you put a quarter of that into a studio. It’d be amazing.

But I don’t know, I work with Americans every day who do it because of the lust of doing it, but I do understand that they’re working in a capitalist society where they can attract investment and the whole notion of attracting investment as an Australian studio is just alien. So then that question becomes where does that money come from? Does it come from the government? I don’t know, that’s a bigger question.

Can you elaborate at all on the pathway one takes to get into doing what you do? Has your journey been a standard one?

Well, I don’t think there’s a standard journey in life, to begin with. I mean everybody’s different, right?

What’s interesting about the game industry, and it’s true of everyone that I work with, it’s that everyone has a different story about how they got there. Absolutely every single person. And what’s difficult about that is that it’s very difficult to replicate, you can’t turn it into a process and tell somebody if you do this, this and this that’s how you get a job.

It just doesn’t work that way, honestly. Part of the reason that I still love working in games is that I feel that, while it’s difficult to understand it sometimes, but I very much feel for the majority that creativity is still celebrated. I feel that the game industry is still one of the ones that will pay you to make music, and in 2019 to make money out of music is extraordinary.

When I was finishing high school, that was where Napster, Morpheus and Kazaa were all kicking up and that was like the nail in the coffin for the music industry, at that point. It was dead. It was done, but of course, it isn’t done because art never dies. Artists never die, it’s always there and seeing so much of this gravitate towards tech and video games has been inspiring.

I realise I’m talking away from your question. All I did in school was play my guitar, that’s all I did. I was terrible at school, I was terrible at everything and I did not have any of the necessary, important skills to get a job doing anything else. So I realised I could make a bit of a living out of teaching guitar and playing in bands but there wasn’t really a future in that. At that age, I was obviously aware of television, film and video games and I was aware that each one of these had music. At that point, I realised that wow, that must be somebody’s job. It must be somebody’s role on that team to create the score for that film, or game, whatever it might be.

So I started sending out demos to some of the companies that were here in Australia. At that time, there was about forty here, there was a lot. At that time they were going overseas for their sound, so they were hiring somebody in the U.S. or the U.K. and they were quite frustrated by the process, it was very expensive and it was very distant because communication was very difficult at that time. So the idea of a local person that could do that was quite attractive to them and I started getting jobs that way.

And it’s pure luck and pure chance that any of that happened, really.

Though brutality of Doom is what you’re best known for today, you’re proficient throughout many genres of music. I think your synth-wave score for Prey demonstrates this. Even if it isn’t heavy metal or 80s sawtooth, what style comes easiest to you as a writer?

You know it’s interesting, I’ve been immersed in music for a long time. It’s interesting talking about it because it’s sort of become like a second language, in a way. I feel personally for me that — this sounds really pretentious, but it’s the honest truth — it’s my first language.

Because I feel I can find what to say musically a lot easier than I can find the right words to say in a conversation. I’m trying to give you an honest answer because when you ask what genre, or what style, I don’t even think about it. It’s all just words and sort of language to me and when we’re on a project it becomes about how to illustrate the world of that game and what language and words to use for that. And if it’s a synthesiser, great! If it’s a nine-string guitar, great. If it’s a string-quartet, great.

Ultimately, they’re all playing the same note. It’s just a different expression of that note.

[Is mind-blown] That’s very true.

Yeah, it’s the language of notes.

So Doom was a brutal blend of heavy metal, electronica, great programming. It was ballsy, angry and noisy. With Eternal, what new ideas did you bring into the studio to expand on these philosophies exercised in Doom?

Earlier this year, I had the incredible opportunity to travel to Austin, Texas.

For the Heavy Metal Choir, right?

Yeah! I was able to, for the first time ever, record a choir of metal screamers and this is something that’s never been done before. It required a completely new approach to writing the music, it had to be written around screamers.

That was a very, very unique, interesting experience. We had twenty-four people in the end. Some of these folks are great, they’re from big bands, you know? It’s a pretty cool thing. How that came about, honestly, we were talking about doing choir stuff on Doom Eternal; we had a little bit of choir stuff on Doom but I always felt it was out of place.

It was there for the token biblical aspect and when it came time to do Doom Eternal we thought what would be a more metal way of doing that. And we thought what if, instead of a brogue choir, let’s just fill it with screamers. Screaming metal, that’s a very interesting texture, what happens if we do that?

A lot of these ideas come about from asking that question. “What would happen if?” Those ideas I feel very fortunate to be able to explore because obviously not every game would support such a thing.

You’ve become known for hiding little easter eggs in your soundtracks. Can we expect more like that with Eternal’s score?

I mean the sheer nature of an easter egg is that it’s an easter egg, right? To some, the easter bunny doesn’t even exist, who would know? Who would know?

Very tactful sidestep. So, you’ve been on the scene for some time, it’s no doubt that it was through Doom you became a household name. Was the whirlwind response to, not only the game but the soundtrack specifically something you expected or were those kinds of accolades and fanfare a shock?

It’s a tricky question to answer, honestly. Whenever you sit down to do any project, your goal is to write the best possible music that you can. To do the absolute best job, there is no second. With that being the goal, I’m going to approach that project the same way, whether it’s Doom or something else. The goal is to make it the best it possibly can be.

Just through the nature of things, when I finish the job and I send the music off to the developers and it goes into the game it’s not mine anymore. I’ve done my bit, that’s it. At that point, you transition the ownership of that over to the fans and if the fans own it like Doom fans tend to do, it becomes its own thing.

They give it a life of its own. We didn’t do any of that, I didn’t do any of that, that’s the fans doing that. That’s the honest answer, it’s very strange. Three years later, people are still talking about a one-fret riff. But that’s another thing I’m really well aware of, it’s that the music in Doom isn’t amazing. But when it has the fortunate privilege of being tied to something like Doom, Doom itself becomes the vessel for any musical idea.

That music by itself is nothing without Doom attached to it.

The opening of Doom is one of the more memorable, kick-arse moments in gaming and I think that’s thanks in large part to the way your score ties to the action so well. I know you’ve spoken at length about the focus to tie music to player input, but how difficult a process is it to pull off?

I mean, with something like Doom it’s a lot easier because Doom is always about the obvious.

Obvious waking up, obvious gun in my hand, obvious demon coming at me, what do I need to do? There’s interpretation in how you engage that enemy next sure, but the obvious answer is kind of there.

There’s always a real rhythm to how Doom plays, which must help?

Yes! And that’s the thing, what you’ve said there. The rhythm of Doom, for sure. What’s the kind of term we usually put on that, it’s like “game flow” or something, that’s kind of boring though.

What I was going to say, though, was that when the answer is obvious, then the music that’s needed becomes obvious. It’s one of those things, I feel like my role most of the time is that of a musical archaeologist. Like the music itself is already done, it’s already there, it’s already written, it just becomes my job to uncover it, in a way.

I feel by the time I’m getting into it, it’s done. So yeah, obviousness.

Whereas with some other games, it’s not always so obvious. One of my buddies, Martin Stig Anderson, who did Limbo and Inside and I worked with on The New Colossus, his whole approach is totally different. He deals with subjectivity, subtlety and ethereal types of things and I think with my high-erratic brain, I don’t connect with music on that sort of level.

To me, it’s a sledgehammer in the face, that’s what I want.

So it is entirely possible though, for other games, ones less intense than Doom, to connect music to player input despite the challenges of more subtle transitioning?

Oh yeah, take those two examples from just before in Limbo and Inside. There is so much going on musically in the background, based on what you’re doing, you don’t even know.

Those feelings that you get when you play those games, that’s the result when that’s pulled off nicely. But that’s not even a thing that’s owned by Doom at all, that’s a very standard way of doing things in games. I feel like Doom is something that really lent itself to the obviousness of that.

The player needs to feel that when they do something, it is the obvious answer. And if the music changes, it’s the concrete confidence that comes with that. There’s no subjectivity with that, it’s straight in, straight to the point.

Do you pay attention to the video game scene at all? If so, do you have any favourite composers or scores from the past year?

Yeah, of course, that’s my job! We’re always up to date with it all. I feel the things happening in the indie scene are really exciting. Other than that, a couple of things that stood out to me were the Kingdom Hearts III soundtrack, that was pretty cool.

Just because it’s so pure to what it is, you know? It’s exciting and crazy, accessible and perfect at the same time. Another I really resonated with was Days Gone. That game went through some development changes along the way but I feel how that story came together, it came out really well.

The use of licensed music in Death Stranding’s quite fascinating, as well. There are games that have obviously done a little bit of that, but they really owned it in that experience. I feel it was to the benefit of the game.

What’s the strangest thing you’ve ever had to do to get that right sound for a score you’ve worked on? Like there’s a picture I can see on your website where there’s a fork resting over the strings of an acoustic.

Oh wow, that’s an old picture I think.

Might be time to update the ole’ site, there.

Yes! Um. [blows raspberry] Seriously, man? I mean, honestly. So, the sound that starts Spinal’s theme is me blowing through a kangling, it is called. A kangling is a Tibetan flute, but it is made out of a bone. A human thigh bone.

So you’ve blown through a human’s thigh bone to make music?

A thigh bone, yes. It took a few tries to get the right human, but after we killed a few we found the right resonant point note. Sorry, it’s the morgue talking. So that one was pretty cool, if you can find a human bone instrument for what is essentially a skeleton character, that’s pretty cool.

There’s a lot of day to day, general synthesis stuff we end up doing that does a bulk of the work. And we’re lucky to have three really cool ancient synthesisers that were made in Soviet Russia. These are amazing because they’re all in Russian obviously, it takes away that direction and the knowing of what you’re actually doing.

Russian will become your third language soon enough.

[laughs] Totally not.

But there’s that sort of stuff. I love just taking a sound and turning it into another sound. The more ways I can find to express and do that, I think is cool. Honestly, there are so many ideas when you start a project of how to do that, what you end up pulling off in the game is 2% of your ideas.

I’ve read stories online of people who’ve reached out to you via your contact section on your site and are surprised to hear back from you at length. How important is it to you to keep an ear to the ground like that in an industry so community-driven?

Yeah, this is what we were talking about before, with secrecy. I get a lot of messages each day and I don’t have the time to reply to all of them but every now and then I just really want to get back to a bunch of people. Because honestly, it’s such a great privilege and honour that people would even take the time to send you an e-mail, they absolutely deserve a reply.

Sometimes I hate the fact that there are just not enough hours in the day to do everything that we want to do. But I think I would really like to see the industry open up a lot more, I think it’d be wonderful to open things up.

I’m currently building a studio, I mentioned it earlier, a horror-themed studio, and I’m obviously building it around the sound aspect but we’re setting cameras up everywhere as well. A lot of my composition sessions and creative sessions in the future are all going to be streamed. I love this idea of engaging with people who are going to enjoy the product, I think we could really take advantage of it and explore new ways we can do that.

The games secrecy thing I always find so frustrating so yeah, I always love that sort of stuff, I think it’s great.

What’s the next little while look like for you now that Doom Eternal has presumably wrapped up?

There’s a couple of things. Obviously the moment the score gets finished, we move onto soundtrack production. So that’s always quite fun, taking the music from the game and turning it into a soundtrack experience. Tackling the Doom Eternal soundtrack is going to be quite exciting and quite fun. Daunting.

So that’ll come first, I have an album that I’ve been working on for a little while that I kind of want to wrap up and finish and push out. I’d really like to, and we’re making steps to, take these scores on the road and do some live performances and select dates.

That’d be cool.

Yeah, do some of this stuff live which I think would be really, really cool. Like, we were talking about that community thing before, engagement in a live setting would be really cool. So yeah, there’s the game projects, I’ve got a studio to finish.

What sort of stuff did you grow up listening to and what drove you to first pick up an instrument?

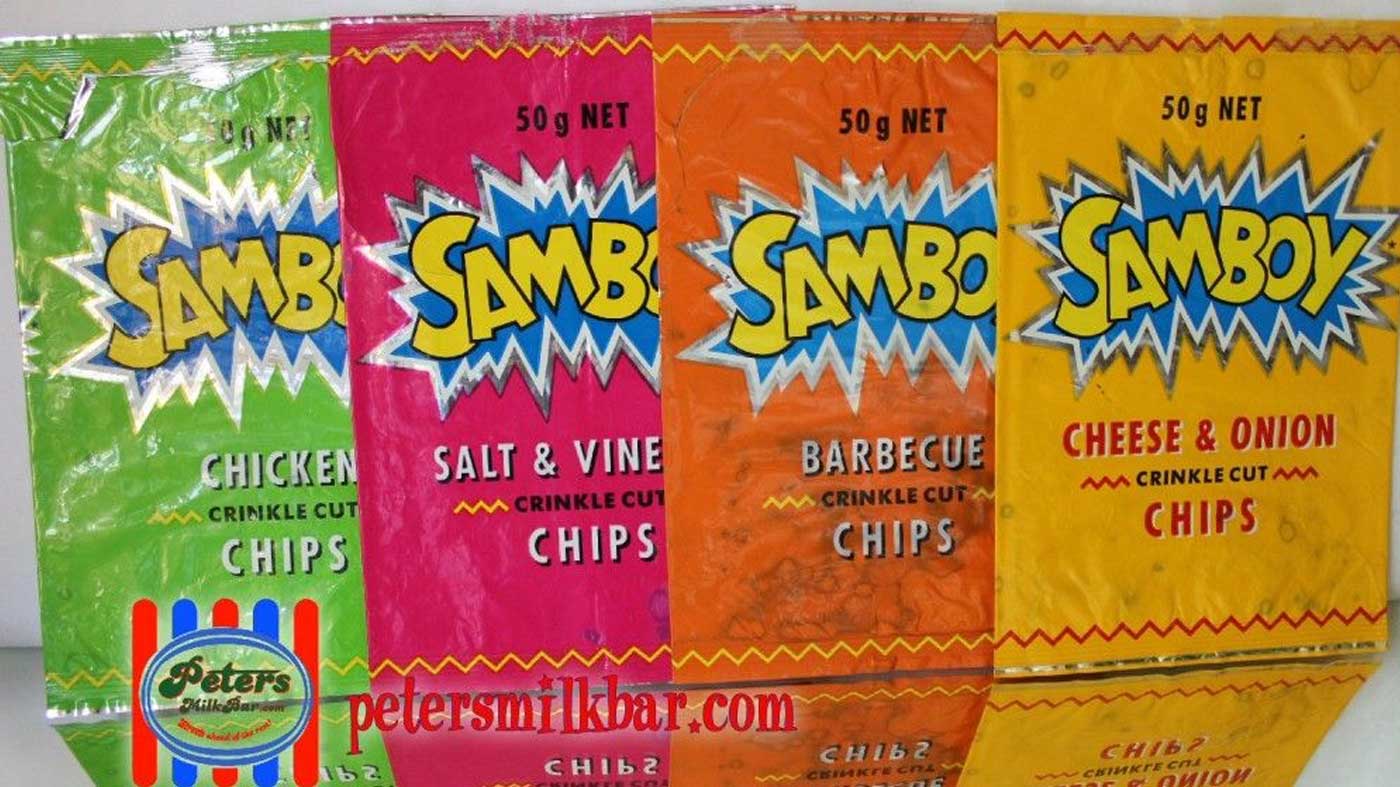

So my first love of music when I was really young would have been hip-hop, believe it or not. I came to that because of, do you remember Samboy chips?

I don’t.

Samboy chips? Come on, man.

Oh, you mean the actual chips? I thought there was a rapper named Samboy Chips or something. Yes, I know Samboy.

Dude, you are so white right now. So Samboy chips, you remember the packets of chips?

[laughs] I do remember the chips, Mick. Thank you.

Yeah right, so they once had a competition where if you collected enough Samboy chip wrappers and then you sent it off, you could win a box of hip-hop cassette tapes. I was about six or seven and I did it, and I won the competition. It was amazing. So I got this box of tapes, a little like Def Jam stuff, I loved it, man. I totally got into that and then later on before I was into guitar, I was kinda getting into Eurodance as everybody was in the late nineties.

Then once I hit guitar it was all blues, man. Stevie Ray Vaughan and Jimi Hendrix, that’s it. And I still sit there and work on things and I ask myself: “Do I need this?” and then there’s a voice in my head that said that Hendrix wouldn’t have used that, he wouldn’t have needed that.

Thanks so much for your time, Mick, it’s been a pleasure.

Oh, thank you man, I really appreciate it.