In an unexpected twist on the regular city-builder trope, Terra Nil is completely free of skyscrapers, bridges, or any other monuments of civil engineering. It’s astutely anti-capitalist in that it dreams up, and has players build, a world that’s handed back to nature. It’s about rewilding, renewal, and recycling, and I think Terra Nil comes at an apt time in our humanity timeline.

As noble as Free Lives’ intentions may be, a niche game isn’t likely to make meaningful ripples in turning the tide against mankind’s slow burn of the only home we’ve got—but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth starting the conversation.

VIDEO PRESENTED BY PLAYSTATION VR2. CLICK TO LEARN MORE.

Contrary to the aim of other city builders, like Sim City where the aim is to build up, Terra Nil’s focus is in leaving an evergreen, ultimately sustainable world behind. Of course, the game still plays mechanically like any builder title before it. An introductory set of tools allow you to introduce wind power and irrigation, creating a fertile landscape for flora and fauna to return.

There’s no “story” to speak of, not that that’s much of a surprise.

After a laborious effort at restoration, you’ll often disembark. This literal handover from the player to nature feels like the idea that’s driven home, and the one constant contribution of mankind, throughout Terra Nil. This is the game’s singular message, that if we left it all behind and vanished, our home would be better off without us. But the other inference is, the planet can’t heal on its own–it needs our help. A lot of “games for change” candidates deal with how we hurt each other, but this is perhaps the best example of how passively damaging we can be.

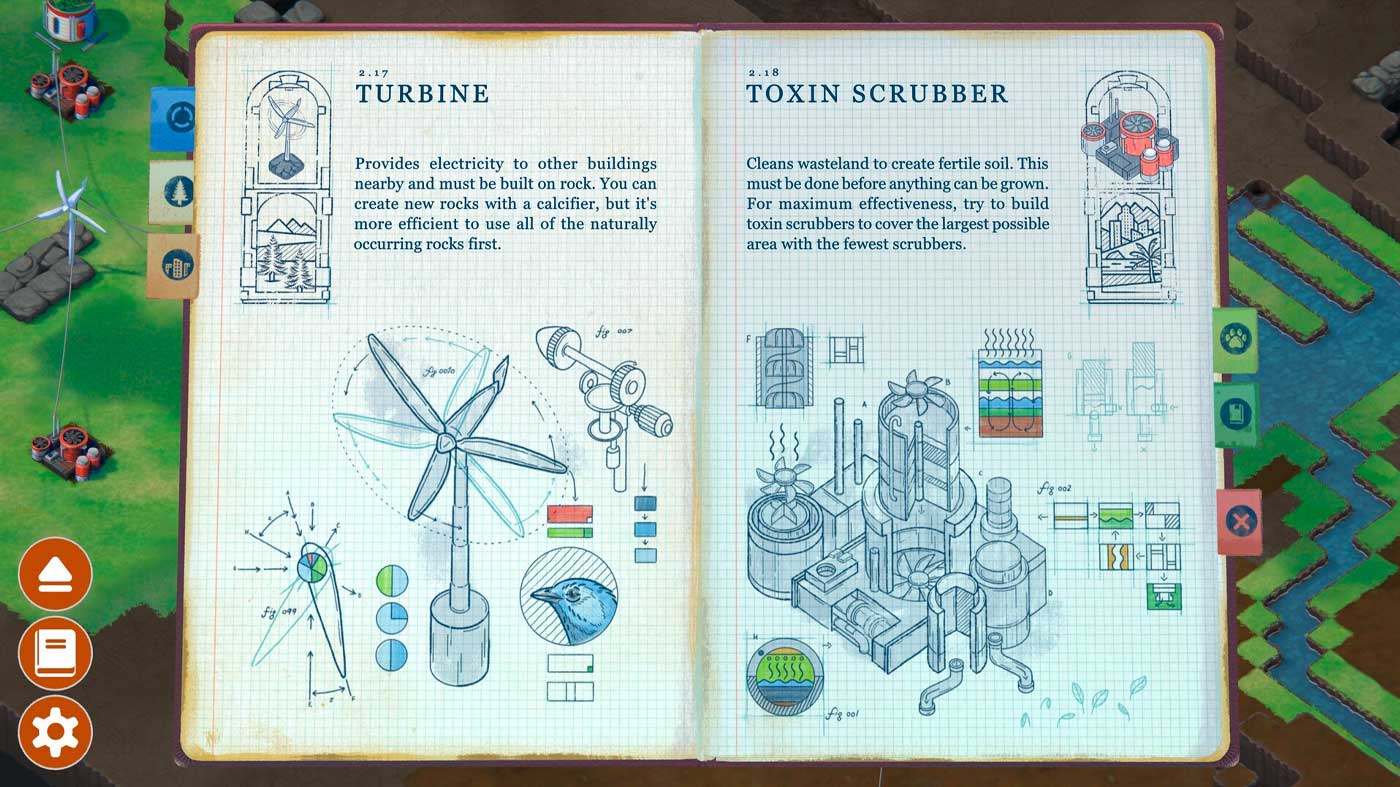

Terra Nil doesn’t assume for a second that city-builders are in vogue, and it does introduce its mechanics in phases before culminating in multi-goal stages that require you to meet varying conditions to cultivate growth. At first, the primary objective is terraforming an arid, tired landscape into a diverse, ecologically sound utopia of sorts. To do this, you place turbines to generate the energy that power the toxin scrubbers which in turn irrigate the soil, it’s a step-by-step journey to creating a lush, emerald paradise. For each tile you convert, you’re awarded points–the game’s only form of currency which is used to place and upgrade buildings.

The next step is creating the biomes and climates that spark the return of wildlife to the area. Whether it’s wetlands, flowering meadows, or dense rainforests, all of the terraforming done has subtle impacts on both the temperature and humidity. Managing these systems becomes a bit of a balancing act, especially if you’re trying for the game’s optional objectives which often require hitting certain markers to welcome the return of particular fauna, like deer, bears, and flamingos. If it sounds like an endless task, it’s not. Once you strike a harmonious balance of biomes and reintroduce enough animals into the ecosystem, it’s up to you to tear it all down, recycle your wares, and leave no trace you were ever there.

The most basic part of the core loop reminds me of Cloud Gardens, a similarly zen game about planting fantastical gardens in the sky, and how its slow grind ultimately gives way to lush, beautiful sights.

The way Terra Nil also delivers its levels as these grand, multi-phase missions of reinvigoration is cleverly devised. Although the mission can be sprawling and quite involved, it holds off ever overwhelming you with too much to wrap your head around at once.

I feel like Terra Nil smartly subverted what I expected from it as a city-builder, as it continues to layer systems onto those already introduced and hardwired into the genre. While I’d purposely call down tornadoes to level my cities in other builders, purposely and efficiently recycling every sign I ever existed to leave a rewilded biosphere behind feels particularly unique. Even after the credits roll, leaving the planet’s restoration curiously incomplete, Terra Nil serves up a series of extra scenarios where the challenge is heightened.

Despite the challenge it can present to efficiently terraform the game’s handful of areas, Terra Nil is a pretty relaxing game and was helpful for winding down after a couple of long days. It isn’t exactly long at half a dozen hours, although there’s a bit of replay value if you’re hoping to reintroduce all species to their respective biomes. Though I might argue the UI is a little bit messy and tough to read at points, Terra Nil definitely is a pleasantly pretty game. Its isometric world view is a genre lynchpin and it’s hard not to be awestruck by the colour and life that you, through your actions, embed into the pixel art landscape. The game’s gentle score, from composer Meydän, is as soothing as a Butter Menthol, and is arguably more peaceful than the tranquillity of a whale’s song.

Terra Nil feels like a short-priced favourite to be the year’s game most capable of inspiring change. With a clear, damning message that we’re no good to our home, I felt Free Lives holding a mirror up to me. I considered my consumption, my waste, and the efforts I could go to to curve my own impact. I feel like the greater statement might have been to launch near Earth Hour to further amplify that initiative.

Terra Nil launches on PC on March 28th.