The infamous Episode Two cliffhanger that has been a wellspring of heartache for Half-Life patrons entered teenage this year. It sat for thirteen long years, unfortunately unresolved, as the industry began to lose hope that Half-Life might ever return. Valve, the series developer, not satisfied with iterating on what came before, spent over a decade working out just how they could break convention to drive the series forward. The only corner of the medium left untouched by Valve’s determined hand was virtual reality, and so their flagship title Half-Life: Alyx was born.

Set after the events of Half-Life’s Black Mesa Incident but before Gordon Freeman’s war march throughout the streets of City 17, and five years prior to the death of her father, a moment that has defined the series for over a decade, Half-Life: Alyx nestles in comfortably as the second chapter of the Half-Life canon. The series is often considered the grandfather of narrative-driven shooters, an early benchmark of dystopic sci-fi that broke new ground in character craft and mind-melting twists. The fashion with which Half-Life: Alyx manages to emulate that clever, cogent style while breaking away from the silent-protagonist trope, is in part credit to Campo Santo. It’s worth noting that key writers rejoined Valve as contractors and consultants, a comforting reassurance that the ship is being steered, into the future, by its original architects.

With Half-Life: Alyx being Valve’s first real dive into the virtual reality space, the hot topic seemed to be in which areas the developer would innovate. It’s such a diverse space with so many variables that I’m pleased to say that Valve’s greatest achievement with Alyx stems not from gameplay systems, plot or graphical fidelity. It comes from just how accessible the game is. If you’re fortunate enough to have a capable set-up (more on compatible setups here), there isn’t much that’s going to impede your ability to absorb Valve’s new take on City 17. If you’ve got physical challenges or even serious space limitations, Alyx really caters to the requirements of just about anybody.

Years before Gordon Freeman would tear through the city and its outskirts with the infamous Gravity Gun, Alyx is kitted out with stylish, fingerless precursor technology, ‘The Russells’. Named after their creator, these gloves can be used to manipulate the gravity space surrounding Alyx as she uses them to pull in supplies from across the room, throw items and interact with the context-sensitive levers, switches, and interfaces within the world. They’re extremely intuitive and help sidestep potential detection issues that can arise from the genre because you’re never going to reach out and pick-up a loose pistol clip when there’s an option to force pull it from a room away. Of course, they’re not without flaw as small, situational and user-controllable niggles will pop up for some, but these are all dependent on the hardware you’re using. This game is built for the Index, so using the Oculus Quest tethered to my machine with a linking cable did prove a trial at times as lack of room beget detection grief, which beget a poorer experience.

For disclosure, I experienced the game through continuous movement with snap turning and a lot of other small settings, like the ability to automatically climb ladders, to assist with comfort. I tried to play the game with complete locomotion but couldn’t develop my sea legs.

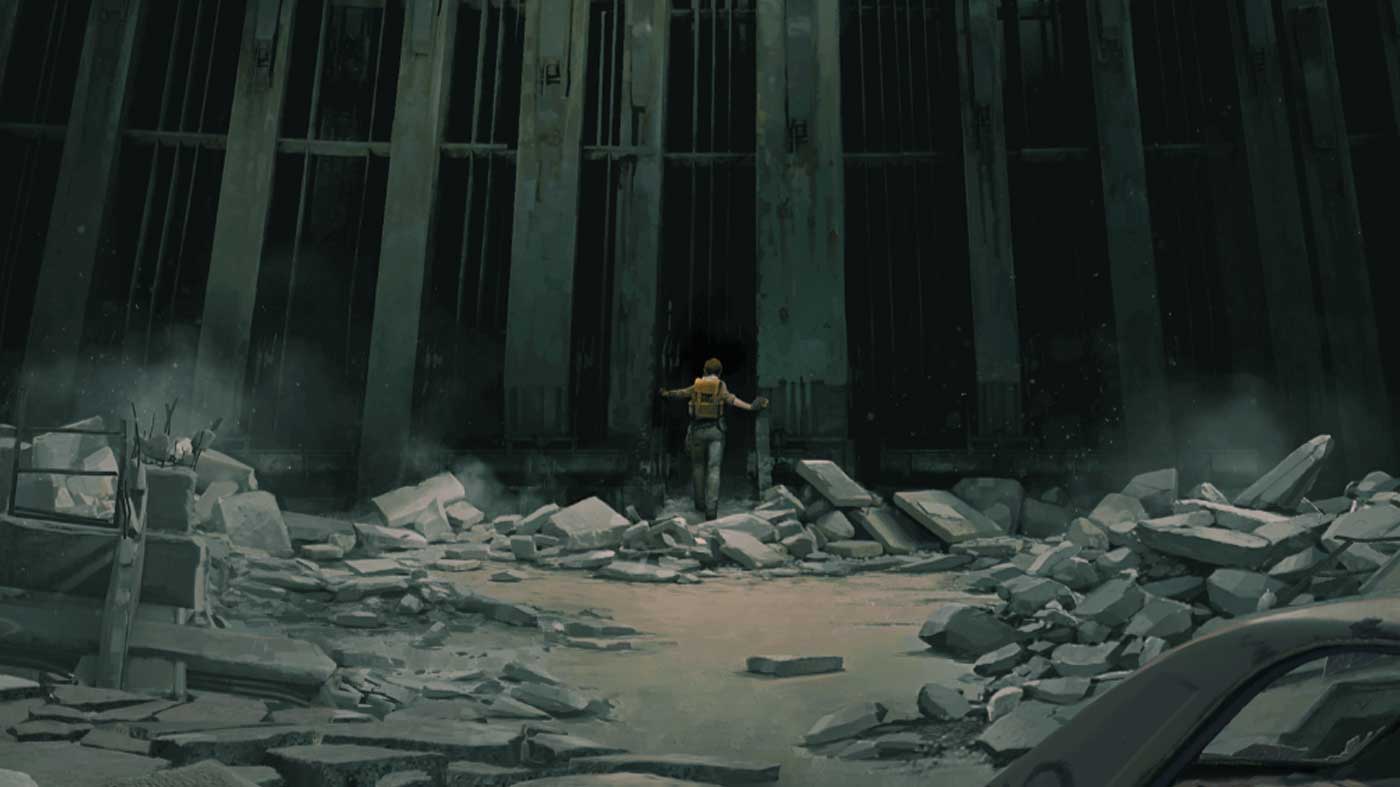

That all said, the world Valve created over a decade ago has been lovingly reimagined for us to traverse in the virtual space and it’s tremendously immersive. From the Orwellian, occupied streets to the city’s underbelly, there isn’t a playspace in Alyx that feels out of place for the Half-Life universe and that doesn’t serve a purpose from a narrative or engagement standpoint. Variety is the spice of Half-Life and Alyx presents each of the game’s eleven chapters as a set piece of its own, whether it’s carefully picking out headshots in a sea of red barrels as you tiptoe through an explosive Xen infestation or hiding from Jeff, a disfigured monstrosity whose eponymous chapter delivers one of virtual reality’s most daunting and atmospheric challenges.

Throughout the course of the game’s ten-hour story, Alyx handles a small variety of death-dealers. Beginning with a gifted pistol from Russell, you’ll later get your hands on a shotgun and a submachine gun. Any of the game’s weapons can be handled one-handed, allowing you to keep your other hand free to interact with the world, and they all feel unique and powerful in their own right. Management of auxiliary tools and munitions occurs with one of two actions. Your backpack, actioned by releasing items over your shoulder, is reserved for spare clips and resin, the upgrade material Alyx feeds into any Combine fabricator to do up her guns. And though it isn’t exactly explained, Alyx is able to store an item in either of her wrists as a small well opens to store grenades stim-packs and even vodka bottles. I never felt as though I lacked the space for anything, so there’s a sweet balance of essentials and superfluous that exists here. Modern problems require modern solutions however, so seeing people filling a small box with grenades and carrying it around like a laid-off office worker speaks to how smart and well-designed a game like this is.

Half-Life: Alyx is great at constantly introducing gameplay elements to keep players engaged, though it doesn’t exactly risk diminishing returns as they often shelf ideas chapter to chapter. In ‘Jeff’, a chapter built around the value of silence, you’re instructed cover your mouth to prevent Alyx from coughing over the Xen spores and it struck me as such an insanely clever mechanic, crafted for a single moment it seems, it was a shame it didn’t really resurface. Perhaps Valve didn’t want to risk even one second of boredom, or perhaps they’re simply throwing concepts into the echo chamber and seeing which resound.

There’s a real sense of atmosphere and immersion in Half-Life: Alyx that Half-Life fans are going to appreciate, though the attention to detail isn’t going to be lost on Valve’s so-called forgotten generation. It’s with zero hesitation that I declare Valve’s return to Half-Life as the best looking game in the series. Of course, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Alyx looks better than its predecessor of thirteen years but it’s the unprecedented detail and fidelity in everything, which is especially surprising for a virtual-reality title built from the ground up. It’s typical for concessions in quality to be made in games like this, but Valve’s uncompromising approach to development, and their steadfast Source 2 engine, means there have been no stones unturned in making Alyx as stunning as it can be. The game’s ability to turn its genre on a dime helped create a lot of sincerely breathtaking scenes that evoked myriad emotions. Though I applaud Valve’s ability to realistically light a scene, gifting me a lone torch only to turn and see ink-black spider crabs trickling in around me isn’t what I needed one night before bed. That said, soaking in the tremendous and beautiful skybox of the cityscape, complete with the mid-air Vault dangling precariously, is a brief pleasure in a game that never seems to take a breath.

After the strong, silent Gordon Freeman, a vocal protagonist is a huge departure for a Half-Life game. The banter between Ozioma Akagha, who does a phenomenal job replacing the original Alyx Vance, Merle Dandridge, and Rhys Darby’s Russell serves as a constant, light-hearted boon in an in-game world so terrifyingly draconian. It’s this banter, which is never so overt that it breaks the illusion, that serves as the subtle exposition and guide to Alyx throughout her mission to save her father. The unswerving, Valve stalwart Mike Morasky returns to score Half-Life: Alyx and there are certainly hints of his prior works under the surface. The low rumblings of fat, compressed synth and programming return from his work on Portal as he manages to combine it with the ambience and feel of prior Half-Life titles.

With Alyx, it really feels as though Half-Life is back. It’s not Valve’s return to form that is anomalous, it’s that they took the break at all. Without missing a beat, this developer, a class above most others, manages to reinvent itself, its craft and breaks new ground all over again, delivering another instant classic Half-Life game. The second that the heavy-set man in the logo turned back, in a state of nature with a valve for a hat, I knew that this game could be special because Valve is a developer that cares.