The Yakuza series has long subscribed to the ethos of narrative and setting first, with gameplay designed specifically to complement those coming in a close second. When it was announced that Yakuza Like a Dragon, the seventh mainline game in the franchise and the first to replace series staple Kiryu with a new protagonist, would also do away with real-time combat in favour of a turn-based JRPG battle system, fans might have been (rightly) concerned. I know I was. It’s nice to be wrong on occasion though, as it turns out that not only is this a worthy entry – it’s the most Yakuza Yakuza game yet.

Like most new crime family inductees, Ichiban Kasuga is an orphan. Raised in a ‘soapland’ where he spends most of his youth playing Dragon Quest in the back office, Kasuga’s life hits rock bottom when his de facto father, the club’s owner, dies. This prompts him to leave school and fend for himself on the streets of Kamurocho, eventually finding his way into the Arakawa family branch of the Tojo Yakuza clan. This is about where the game begins, with Kasuga working small-time beats for the family in the very red light district that series fans will be all-too familiar with. Kasuga’s life as a young Yakuza isn’t exactly glamorous, in fact it’s a lot more fetching toilet plungers and chasing down fake porn peddlers more than anything, but he quickly finds himself with a bigger job than most – taking the fall for a higher-up in the family and going to prison for 18 years.

Those heroic aspirations carries him through at least one more life-altering event after his prison term too, as a betrayal quickly leaves him for dead in an entirely new location, the Ijincho district of Yokohama. The game’s lengthy introductory chapters have a big job to do in setting up a brand new main character in this established series, but the most important groundwork laid is Kasuga’s obsession with old-school JRPGs and its significance as the lens in which he views the world, especially having spent the majority of his adult life in jail. There’s no shortage of irony in a protagonist who’s obsessed with being a hero but has been raised on Yakuza values, giving him an entertaining and ultimately endearing-ly warped perspective that results in one hell of a character arc.

I hesitate to delve too much into the game’s overall narrative (these games don’t deserve spoiling in any capacity) but what follows is very typical of the series, rife with clan wars, political intrigue and more than a few holy shit moments. Some of its big reveals, especially in the game’s latter half, require such strong suspension of disbelief it might as well be expelled, but that’s Yakuza in a nutshell. The story does benefit heavily from being something of a fresh start, meaning you don’t need a series worth of knowledge to fully engage with the story, but if you’re going in with experience you’re sure to appreciate the nods to entries old that range from subtle to an emphatic “Did that just happen?!”.

The district of Ijincho where you’ll spend the majority of the game is also an extremely interesting setting rife with tension and turmoil, as the de facto home of displaced Chinese immigrants pushed out of Yokohama’s Chinatown who find both kinship and purpose in a trio of controlling crime families. It’s probably one of the most diverse settings in the series and easily has as much personality as Kamurocho. Gorgeous waterfronts, city centres, restaurant strips, slums and highways add up to a far bigger single area than I can recall experiencing in a Yakuza game. Just be careful crossing roads – you can totally be hit by cars again.

So far, so Yakuza. But if you’ve been following the release of Like A Dragon you’ll already be well aware that this isn’t the same Yakuza that fans know. In an impressively bold effort to support Kasuga’s character and narrative, the game features JRPG-style turn based combat instead of the usual real-time brawling. It’s a huge departure, and one that long-time fans might rightly be apprehensive of, but I’m happy to say that it absolutely works.

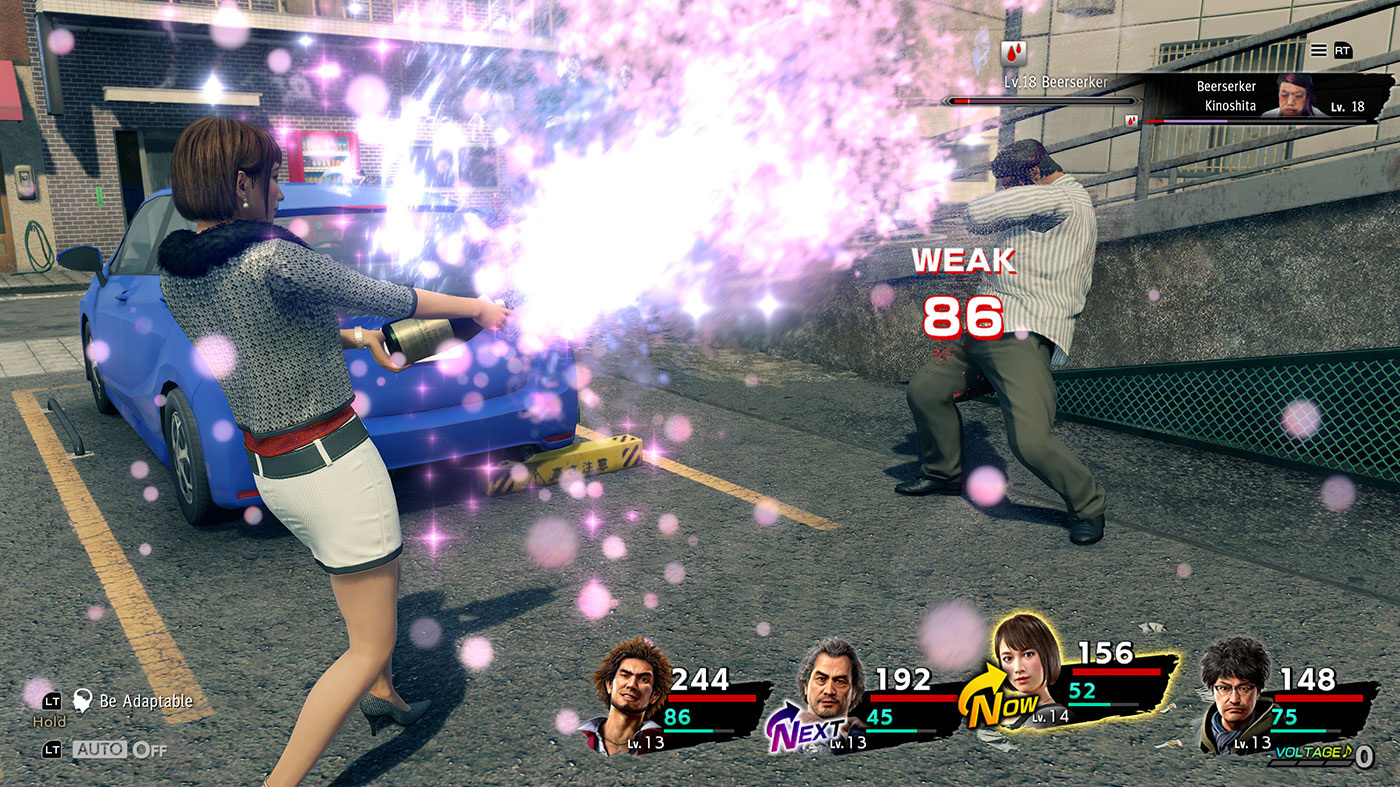

There are two sides to what makes combat in Like A Dragon make sense, starting with the full context of its narrative. We know that Kasuga and his newfound crew aren’t actually waiting their turn to get a punch in when they’re rumbling with thugs on the street, rather what the player experiences is our hero’s unique perspective made tangible in the mechanics of the game. From the way random crims and creeps on the street seemingly transform into outlandish caricatures with delightfully-bad pun names like Steamed Punk and Dotcombatant to the menagerie of mundane items like soup ladles, wine bottles and even the odd ‘massage wand’ standing in as powerful weapons, there’s no pretense of realism here. It’s all a game to Kasuga, and it’s quite literally a game to the player, so why not embrace that?

This is bolstered by a job system that takes the idea of job systems very literally, forcing Kasuga and co to attend a job placement program called Hello Work that helps them enrol in a variety of new career choices ranging from bar hosts/hostesses to chefs to street musicians. Like enemies, the party transforms themselves into these roles when a battle starts, and half the fun is just seeing these characters dressed up in what amounts to vocational cosplay complete with the aforementioned ridiculous weapons and themed abilities.

The other side of the combat equation is simply that it’s still a ton of fun. Despite the shift to a turn-based system, it’s anything but passive. The way a battle pans out isn’t solely dictated by the actions you pick for your party members, with plenty of opportunity for shenanigans both intentional and otherwise. Taking a leaf from the Paper Mario games, characters’ unique abilities can often be made more effective by executing command prompts in time, which goes a long way to making combat feel more involved. Positioning also plays a critical role with classic Yakuza environmental objects like bicycles and traffic cones still coming in handy – if there’s on object in-between a party member and their chosen target they’re likely to make violent use of it along the way. Likewise if an enemy gets in the path of an attacking there’s a good chance they’ll interrupt the move, or get swept up in it, and vice versa.

This all adds a much-appreciated but unobtrusive layer of strategy and viscerality to combat that goes a long way to make what could have been a jarring transition feel more like a natural side step. Having a whole party to play with works really well with a lot of traditional Yakuza systems too, like touching base with people in bars – when you chat to your team mates at Bar Survive not only do Kasuga’s personality traits level up but his bonds with the others strengthen and that in turn gives them bonuses like passive EXP gains and new job aspirations. It borrows as much from games like Persona as it does Dragon Quest, not least when you start finding actual Persona soundtrack CDs to play at the bar while you work on your social skills.

There’s even a whole, optional sewer ‘dungeon’ not unlike Persona 5‘s Mementos that’s made available for grinding EXP. You’re first introduced to it in an early-ish chapter, as part of the story, but you’re able to revisit it nearly any time. The unfortunate thing is its grey walls and repeated corridors are super boring to look at, and not overly fun to play in either. I never found that I really needed to venture down there, and a dungeon built specifically to get around an imbalance in the game’s challenge climb works as a silly homage to the concept in other RPGs. Still, from a fun perspective it’s… well, it’s just not. Especially when the very first time you’re forced to run it as part of a story beat is the longest and least interesting go around, and will probably make you never want to go back again.

So that’s a lot about what’s new in Yakuza Like a Dragon, but diehard fans should fear not for this is still very much the series they know and love. From a structural point of view, not much has changed. The game’s fourteen chapters are rife with opportunities to be distracted, whether it’s exploring character side stories, helping out Ijincho citizens with their troubles, unwinding at a Club SEGA with playable arcade classics like Virtua Fighter 5 Final Showdown or getting in a few rounds of karaoke. Nearly every staple mechanic has been carried across either wholesale or rolled into the new systems in some way, which goes a long way to making its massive departures feel a lot less massive.

New mini-game content runs the gamut from a seriously-involved business management sim that sees you answer to a chicken named Omelette as well as a Mario Kart clone called Dragon Kart. The latter is a personal favourite of mine, not only because kart racing is a ton of fun but because it’s wrapped up in a dramatic and personality-filled storyline to rival the most intense sports anime.

Like a Dragon is also an impeccably-presented game, as you would expect from the series’ modern entries. Utilising the same engine that powered Yakuza 6 and Judgment, the streets of Ijincho are dense, intricate and full of life. It’s the character models and animations that continue to be a highlight though; in the game’s impressively-cinematic cutscenes they’re rich in detail and personality, and their animations in traversal and combat are both masterfully-crafted and super stylish. When we previewed the game a few weeks ago we played on both PC and the Xbox Series X and came away very impressed, and while the game running on a PlayStation 4 Pro for this review definitely comes at a cost of resolution, framerate and some texture detail but it still looks fantastic. The occasional pre-rendered cutscenes also stick out far less on a current-gen platform than they do on the newer hardware where video compression and a lower framerate can be jarring.

The game’s English cast do a commendable job nearly across the board, lending charm and personality to the characters, though Greg Chun’s version of Nanba took a bit to grow on me. The inclusion of an English dub at all, something the mainline series hasn’t had since the original release of the very first game, is a sign of commitment from Sega of America that’s almost worth double when you consider how much more batshit this entry is compared to the last. The English translation is stellar as usual, delivering the narrative with exactly the right mix of nuance and goofy humour and even taking some hilarious creative liberties with scenes in the game that might’ve otherwise played awkwardly. The team has clearly had a lot of fun with some of the incidental text and dialogue too, with an abundance of puns and plenty of references for the Yakuza fandom (and plenty of others) to pick up on. Plus, an English dub means we get English versions of the game’s karaoke tracks and… well, they just need to be experienced.

That said, there’s definitely content here that Western audiences might find more objectionable and/or uncomfortable, which again won’t be new to series regulars, and the game does at least highlight this in a splash screen when it boots up. Cultural differences, especially when it concerns things like gender power dynamics and the treatment of sex workers, are seemingly baked deeper into the game’s identity than a translation can dig out.

So much of both Kasuga’s story and the setting of Ijincho centres around its homeless community, which winds up playing a fairly big part of the game, and is something that might not land the same for Western audiences. I’m on the fence about whether its representation is explicitly malicious in moments but, even in the English text, there are a fair few throwaway jokes and flavour texts that feel out of line. It tends to turn on a dime between being an earnest portrayal of homelessness and then giving you a Pac-Man inspired can collecting minigame and enemies named “Hungry Hungry Homeless”.