RAD takes place during the 80s in an alternate history, where most of the major civilisation was wiped out by a catastrophic nuclear event. Those who survived have come together to rebuild society using effigies they call respirators. You play as one of the survivors as they embark on this journey in a foreign land that’s permanently stuck in the 80s (culturally speaking). The goal? To gather enough resources to bring the machines that will help develop your civilisation into what it once was. The twist? You’ve been enchanted with the ability to absorb and mutate from radiation rather than being harmed by it.

The story is simple but gets the job done. More surprisingly, there’s a comprehensive codex of sorts called the Tome Of The Ancients that fleshes out the world of RAD if you’re that way inclined. I personally didn’t find it necessary, as this is really a game where gameplay is first, but it is a nice touch if you need some extra context for what’s going on around you.

Rad plays like a typical roguelike – a genre that’s a dime a dozen (especially in the indie space). You take your character on an adventure through a procedurally generated world as you gather resources before you inevitably die. The key idea of any roguelike is that with each death, you use what you’ve done to grow a little stronger and get a little bit further on your next run until you inevitably win. It’s a simple concept that’s not for everyone, but there’s something oddly addictive about it. RAD is a little bit different in a few ways, though in largely superficial ways. As such, it does feel like a game you’ve probably played before in some capacity – be it something like Binding of Isaac or Spelunky.

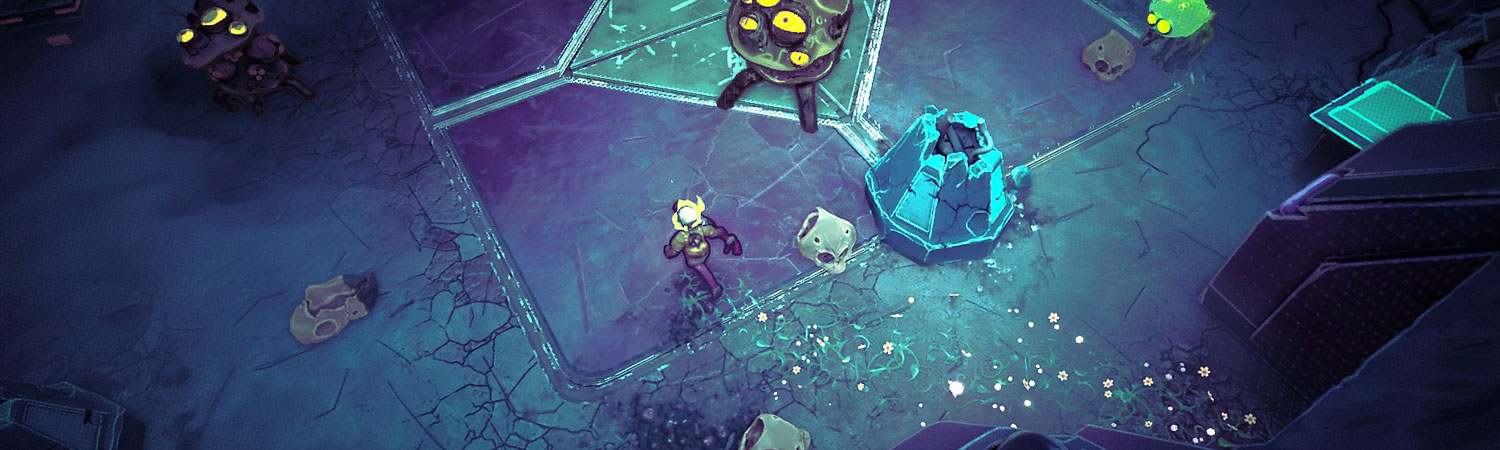

As mentioned previously, every time you go out on a run, you’ll notice the whole world changes. The game is procedurally generated, meaning that the overarching structure of your progression will be the same but individual levels and enemy placements will not. This random element is carried over to the abilities you’ll unlock, which are on the more bizarre side as the idea is that as you absorb more radiations, you spawn more mutations.

Mutations themselves come in two flavours – actives ones that are tied directly to new abilities and passive ones that offer buffs (and sometimes debuffs). The most common one I came across let me poop out fish eggs, that then hatched into little spider versions of my character to assist me in battle. Others let me leave behind a trail of toxic slime, a second brain lets me slow time, while another let me glide as I sprouted demonic wings. The mutations themselves are all grotesque, but in a weirdly endearing way with the same style of humour I’ve come to expect from developer Double Fine.

I previously eluded to the fact that with every run you get stronger, and in RAD that happens in a few different ways. After you die (and you will die) you’ll gain points which allow you to unlock new items and abilities to purchase from vendors. You can also return to your camp and deposit your money, which, by the way are cassette tapes, so that you don’t lose it all when you die. Such strategies can eventually lead to purchases of other weapons, some of which level you up faster and remove the monotony that would generally arise from repetition in a game like this.

Other little things contribute to the real sense of progression and achievement in RAD. For one, the more you spend at the stores improving yourself, the more money you’re putting into the city. As such, between runs, you’ll notice the town itself improves as the people find more to do with the currency you’re handing over. Motivation is key to retaining players in games like this and it’s these little details that make you feel like you’re actually getting somewhere in RAD, despite dying so many times.

While I mentioned that you’ll probably die in RAD, you can adjust the difficulty whichever way you want with the quirks system in order to hit that sweet spot. Quirks can make the game significantly harder; such as preventing you from mutating at all, while others might double your health. Quirks feel like an easy way for players to design their own difficulty mode as they see fit and a way to leverage your own style of play, be it combat or exploration, with the way the game is difficult. I love them, honestly.

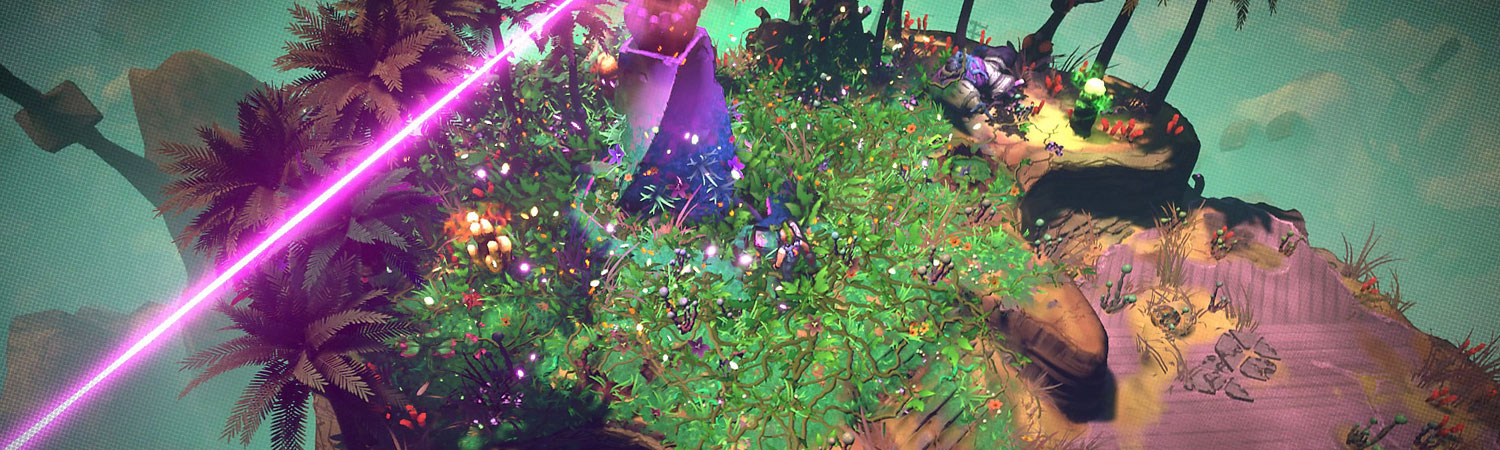

If you haven’t worked it out already, the title RAD is a double entendre. One of those meanings no doubt eludes to the game’s bright and colourful, 80s inspired aesthetic, and it’s one of the standout things about RAD. So many games are realising that a brown post-apocalyptic wasteland isn’t fun to explore anymore, and RAD is contributing to that trend. The worlds you’ll explore are drenched in bright neon colours and the characters, even if cliché, fit all the archetypes from the best films from the 80s. If you’re a bit older, or a bit nostalgic, just looking at RAD might be enough to entice you to dig deeper into it.

It’s just a little bit of a shame that there’s not a whole lot of variety in the environments you’ll explore. While procedurally generated content does irk me, I can usually put that aside if the art and the assets are engaging. Unfortunately, in RAD, there are only three major level types to plod through. And in a game that has you running through it multiple times, this lack of visual variety can be a little grating during longer play sessions.

As you’d expect, the audio design is cut from the same cloth. You can expect electric guitars, energetic synthesisers and an overbearing announcer who just won’t shut up. But that’s all fine because it all dovetails wonderfully to help make the experience feel ever so authentic.

It’s that sense of “just one more” that really determines whether a roguelike is worth your time, but with RAD it’s unfortunately not a guaranteed feeling you’ll walk away with.