Press Start may receive a commission when you buy from links on our site at no extra cost to you.

Rarely does a game come along that’s as unique and wonderful as Romeo Is A Dead Man. A game that, despite having some very obvious technical flaws, somehow manages to transcend said flaws to offer up an experience that is truly like no other. While fans of No More Heroes probably have an idea of what to expect with Romeo Is A Dead Man, it’s the way that developer Grasshopper Manufacture manages to still surprise you decades on since their inception that makes them so good at what they do.

Romeo Is A Dead Man follows the story of Romeo Stargazer, who is fatally wounded by a monster one night. Just before he dies, he is saved by his scientist grandfather, Benjamin, by injecting a life support system into his eye. The system essentially turns Romeo into a kind of Robocop, bringing him back to life but supporting his damaged organs with machines. But having lived through such an attack, the space-time continuum is shattered, and Romeo finds himself becoming a Space-Time special agent for the FBI. His mission? To track down his girlfriend, Juliet Dendrobium, as she and others who appear to be her appear across different timelines.

It’s hard to summarise what Romeo Is A Dead Man is about succinctly, and I barely have scratched the surface above, but needless to say, it’s an absolute trip. Like No More Heroes, Killer Is Dead, and even Shadows of the Damned before it, Suda knows how to tell a story. It doesn’t necessarily make sense when taken at face value. While I enjoyed the trip that Romeo Is A Dead Man took me through, I’m still not entirely sure what it was trying to say. I adored the absolutely batshit direction that Romeo Is A Dead Man takes, but I’m never a huge fan of time travel storytelling, even as someone who has loved every Grasshopper game prior.

But beyond the story, Romeo Is A Dead Man feels like a spiritual successor to No More Heroes in many ways. While Travis Touchdown’s story has well and truly concluded, the gameplay and storytelling of Romeo Is A Dead Man feel awfully similar. There are levels to explore, bosses to battle and, of course, minigames to play. Instead of climbing the assassination leaderboard as Travis did, Romeo is essentially sent back in time to clear an anomaly from the timeline. All of these systems feed into the gameplay loop in meaningful ways, both narratively and mechanically, though while there’s a lot about Romeo Is A Dead Man that’s similar to No More Heroes, there’s also a whole heap that’s different too.

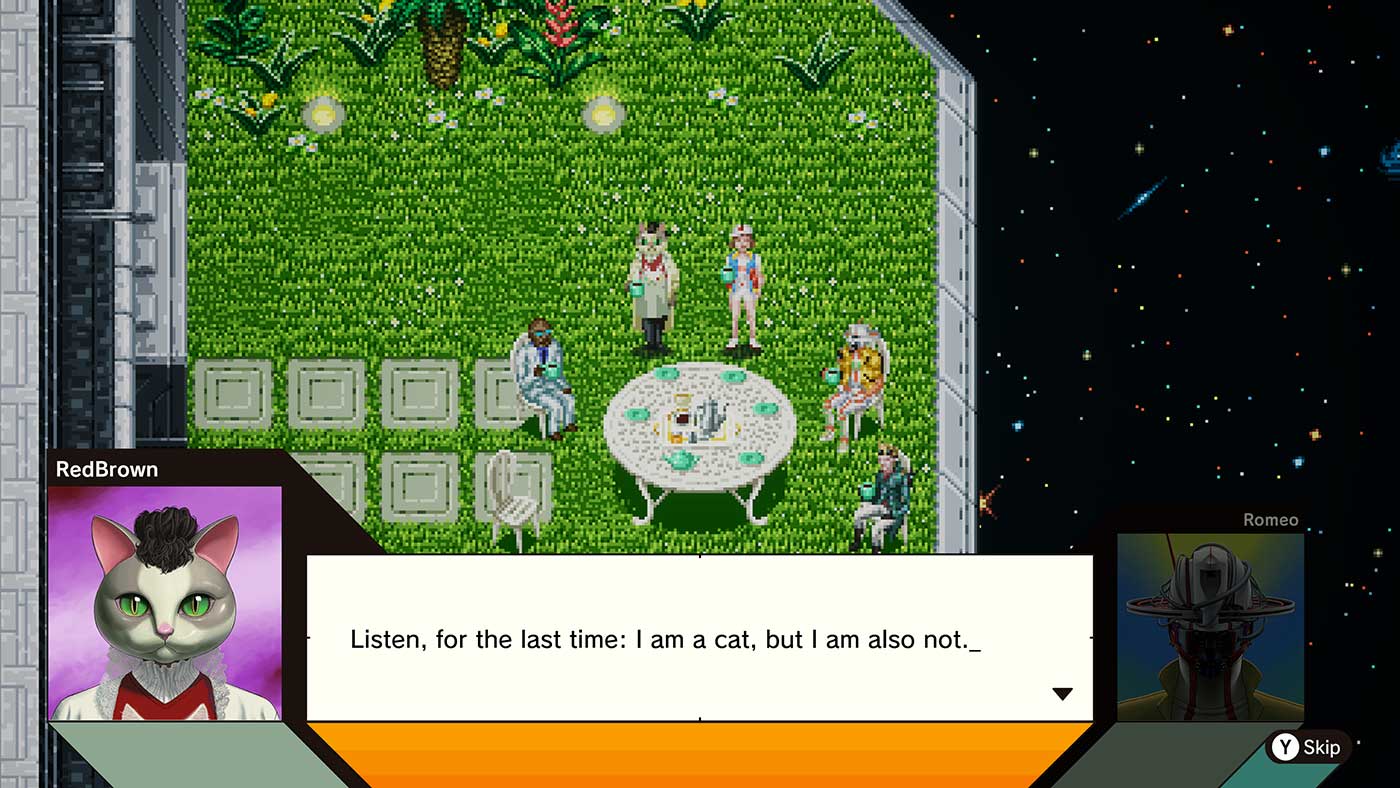

In typical genre-bending fashion, you’ll begin every chapter on your ship. Rendered like a top-down 16-bit era game, complete with quirky pixel art, you’ll be able to explore the ship as Romeo and speak to everyone on board. Some of them will sell you stuff, others will allow you to grow Bastards (more on that later), and others let you cook katsu curry to take with you into the field to improve your stats. It all sounds random, though unsurprising if you’ve played a Grasshopper game before, and comes together in a way that is a simple and satisfying way to spend your downtime.

When you’re sent out on a mission, usually in a different time period, you’ll navigate your way through space in Star Fox-esque sequences in which you have to fly the ship to the dimensional tear to travel to the time period the FBI has sent you to. Most of the chapters will have you exploring an area, collecting parts of an interdimensional key from subspace and subsequently defeating a boss. It feels like a blend of games like No More Heroes, though Romeo Is A Dead Man does a better job of giving players something to do when they’re not fighting bosses. Levels draw inspiration from plenty of other pieces of media – including Dawn of the Dead, Resident Evil, P.T. and even real-life events like the Jonestown cult. There’s a nice selection of light puzzle-solving, though nothing too taxing.

One thing that doesn’t work as well in Romeo is the idea of the subspace. It’s an area that exists “underneath” each of the levels you’ll play, like a “dark world” in other games. You’re transported to these areas through an old television to find the pieces of the key that you need to fight the boss in each chapter. They’re visually quite busy, taking on the appearance of a living, pulsating wireframe world, but they are also difficult to navigate visually, despite being linear. They’re the smallest part of Romeo Is A Dead Man, but perhaps still my least favourite, as they don’t really have any rhyme or reason to their design. That’s the point, artistically, but practically, it doesn’t quite work.

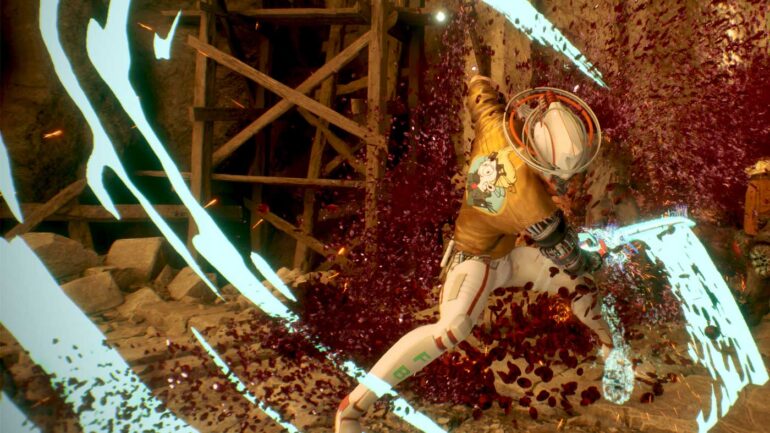

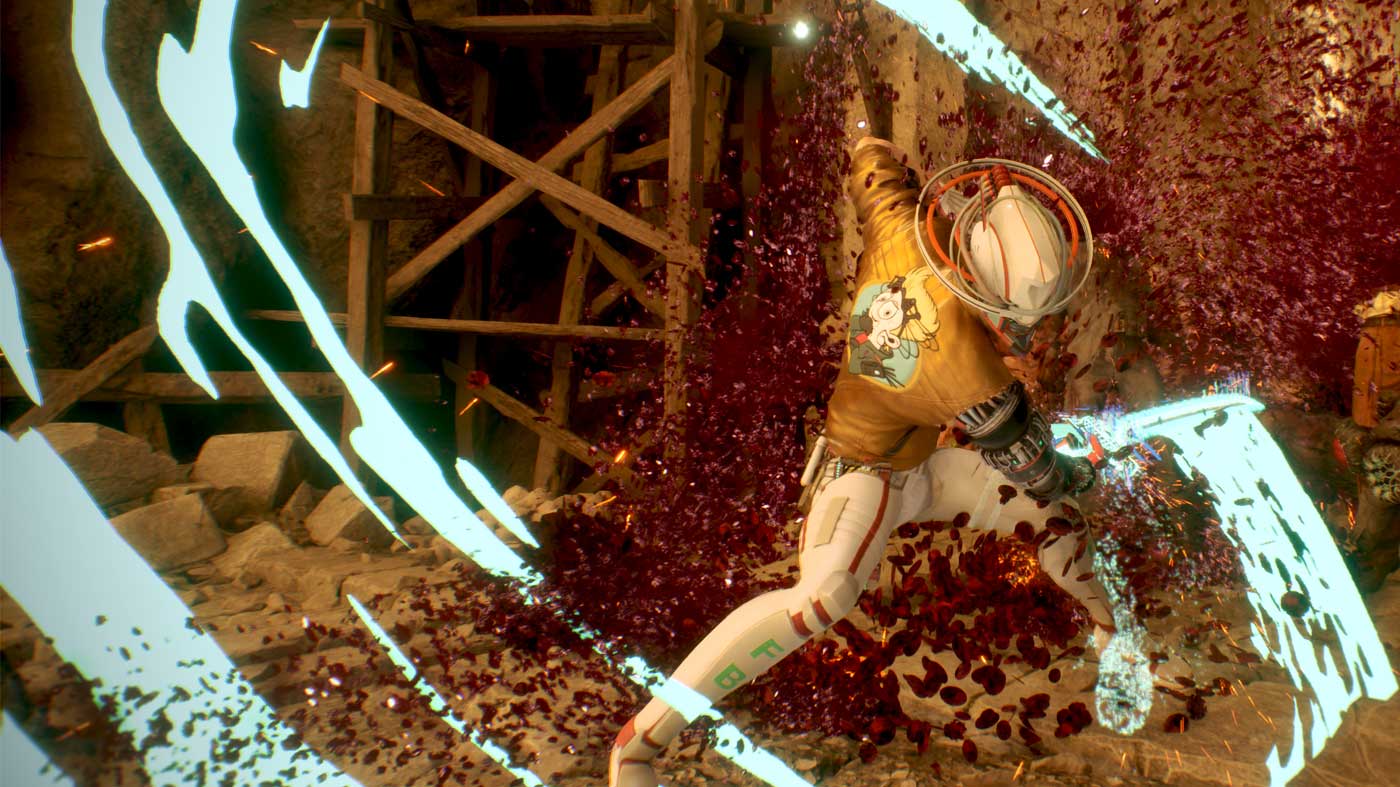

The combat, on the other hand, feels great. Again borrowing quite a bit from all the games that have come before it, the game combines both melee and projectile. Bizarrely, but in a move I very much appreciate, you can unlock all the weaponry and guns you need early on, allowing you to experiment and find your favourites quickly. The general flow of combat is strong – you have a dodge and moves that build up a blood meter, which can then be used to recover health. It’s a clever combat system that rewards aggression over anything else, though you can unlock health-recovering consumables if it’s a system you don’t want to engage with.

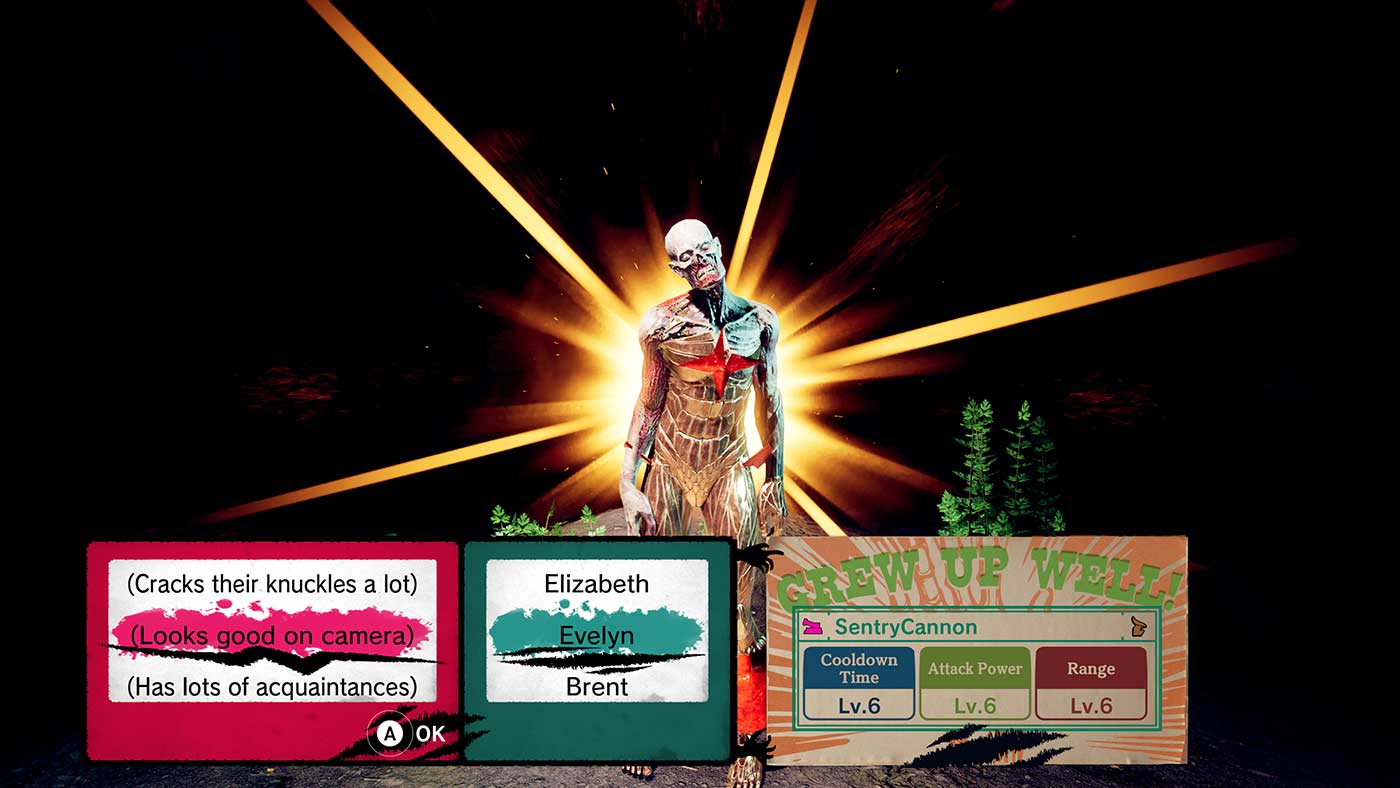

The other side of the combat is the “Bastards” system, in which Romeo can take up to 4 different zombies into battle as sub-abilities. These “bastards” are grown on your ship in an Animal Crossing-esque minigame. The longer you leave them to grow, the more powerful they become. Each Bastard has a unique set of stats that affect its special ability – some can be sentry guns, others might slow the enemy down or inflict poison. There are quite a few, and when you have heaps, you can even have them consume one another to improve their stats. It’s a fusion system akin to Persona Fusion in the Persona games, albeit a whole lot less elegant, but it can help you augment your combat abilities in a way that best suits your style, too.

And you’ll really have to commit to your stats and the like here to be successful. This may be because I played on Hard, but whenever I hit a boss, I would have to go back to the drawing board and essentially retool Romeo to better suit the boss I was facing. Even after doing so, bosses do feel quite spongey from time to time, and them only having one or two weakpoints before having to start relying on dealing regular damage can get tedious. I suspect this might be less of an issue on the lighter difficulty levels, though it’s worth mentioning for those who play on hard.

That being said, there are plenty of ways to level up Romeo and his weapons if you know where to look. There are multiple dungeons, randomly generated, called the Palace Athene, in which you can take on rooms of enemies to earn experience and items to improve your weapons. On one hand, I felt the need to grind could put some players off, as it’s something I’ve never needed to do in other Grasshopper action games. On the other hand, the action is so steadfast that I didn’t find it off-putting to have to be put through the gauntlet a few times between bosses. The Palace Athene can be adjusted in difficulty to improve rewards too, which is a nice touch.

And while artistically, Romeo Is A Dead Man is an achievement for Grasshopper, like their other games, it does have some unfortunate performance issues. With every enemy spitting out numerous pixels of blood with every attack, things can get visually busy very quickly. When that happens, you can expect, slowdown and to have to wait some time until the framerate stabilises. As somebody who slugged it out with No More Heroes on the Wii or Killer Is Dead on the 360, I don’t personally mind this aspect, especially as the game looks so good. But if you’re sensitive to these kinds of performance issues, it’s worth holding out until a few optimisation updates hit.

While Romeo Is A Dead Man isn’t quite the masterpiece that Grasshopper was hoping for, it’s still an incredible journey that really highlights why Suda51 is revered as the artistic force that he is. It’s a game, like many of his, that is bound to be divisive. But as a long time fan of everything the auteur Japanese studio has done, it’s a joy to see them continually hone their craft.