Press Start may receive a commission when you buy from links on our site at no extra cost to you.

As someone with a soft spot for Priscilla, our country’s crowned jewel, ‘Queen of the Desert,’ the smooth blend of Australiana and adventure is something I’m drawn to. The Drifter, the pulp-thriller point-and-click game out of Melbourne developer Powerhoof, riffs on the classic novels of Crichton and King and so-called Ozploitation films of the late seventies and early eighties. The quaint sliver of unspecified Australia put forth in The Drifter proves to have an irresistibly dark underbelly that’s heightened by synth-driven nostalgia; however, it’s the team’s willingness to ratchet up situational tension that leads to a story and game that’s unforgettable.

After stowing away in a boxcar to get home for his mother’s funeral, Mick Carter’s homecoming takes an unexpected turn after he witnesses a shooting before being pursued, captured, and left for dead in a nearby reservoir. After water fills his lungs, Carter regains consciousness once again—moments before his death—with a chance to defy fate.

He narrowly escapes death’s grasp to find he’s been framed for the boxcar murder before getting drawn into a grand science-fiction conspiracy. Beat-to-beat, The Drifter is a rollercoaster that maintains tremendous momentum throughout its gloriously paced ten to twelve hours.

Carter’s sad history and reluctance to confront his own past make him a rather sympathetic battler, and I appreciated how it’s his specific desire to forget that’s the catalyst for the game’s events.

The deeper he makes it down the rabbit hole unravelling the mystery that’s core to the game, Mick is surrounded by an endearing, albeit ragtag, crew of helpers—Detective Hara, the investigator seemingly flown in from overseas to investigate the case, fast became a favourite character of mine, there comes a point that he, through a compelling mix of curiosity and loyalty, is simply along for the ride and The Drifter is better when he’s on-screen. Although I initially took issue with the game’s final act becoming a “bottle episode” of sorts, as you occupy a single location throughout multiple chapters, I loved the game’s climax, in retrospect.

For a story that, at every turn, subverted what I expected it to do, the last act’s boldness to revoke the sense of already limited freedom you had to create a surprisingly claustrophobic finale, where the stakes are felt, made for a genuinely exciting conclusion.

The Drifter, despite being inspired by classically designed adventure games like Monkey Island and Broken Sword, manages to respect genre norms while implementing modern ideas. It utilises a twin-stick approach which grants free movement on the left stick, with the right stick serving as the context-sensitive, and very accessible, action wheel. Like any adventure game worth its salt, The Drifter has incredible puzzle design that’s driven largely by lateral reasoning, item management, and item combination. I’ve felt in the past that games like this can be a bit obtuse; however, I don’t think there was a single solution in The Drifter that didn’t feel earned, which is the hallmark of intuitive, thoughtful design. If the height of bullshit is Monkey Island’s famous monkey wrench puzzle, The Drifter quite deftly avoids similar pitfalls.

So much of The Drifter’s allure comes by way of short, tense, time-sensitive sequences that force you to panic, die, get reborn, and fumble through outcomes until you escape intact. I think the way that the death loop gimmick is integrated into gameplay, as it is the narrative, is quite clever and fun. The aforementioned reservoir scene is the first example of this, as you race the clock to slip your bindings before drowning—your inventory early on makes the solution a straightforward one, although the shock of the urgency lingers.

Although many adventure games have dialogue options for you to feel your way through the mysteries of the world, The Drifter’s way of handling Mick’s pursuit for intel is a little neater, I feel. As you gather talking points, for want of a better term, Mick will be able to use them as jumping off points to question key characters, which, more often than not, generates greater leads to progress deeper into the plot. You’re also able to pull up the talking points at any point, which gives a short overview of the most current tidbit Mick heard.

If there’s one thing The Drifter captures immaculately, it’s atmosphere. Although I don’t recall the game establishing a time and place, it straddles eras courtesy of a deliciously dark, synthwave soundscape, which evokes a Carpenter-esque period of cinema, while its technology, mobile phones, laptops, and the like, definitely call to mind a certain point in Australian history.

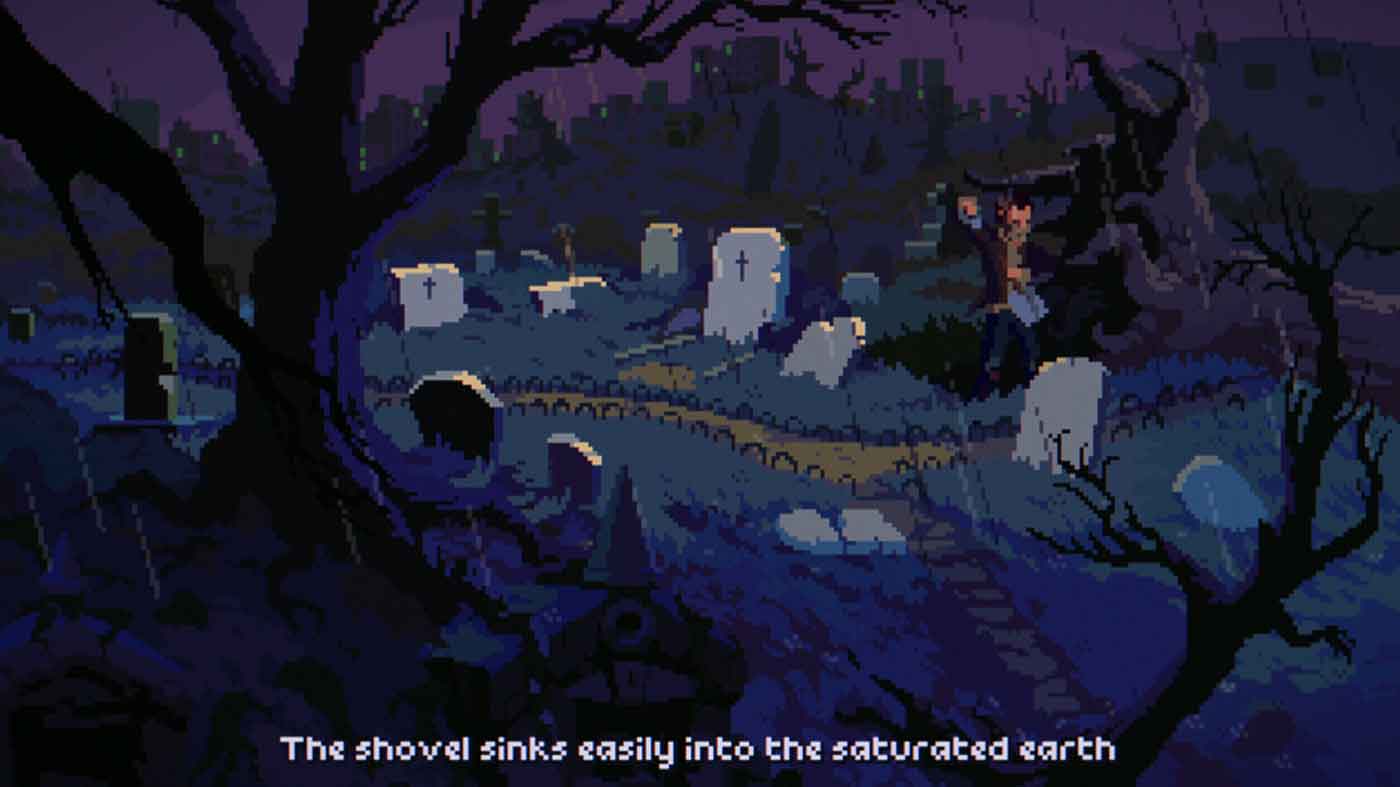

Barney Cumming’s contributions to the game, through art direction and animation, cannot be understated. The Drifter is seriously gorgeous and delivers a pixel art experience that’s both visceral and arresting. Similarly, the background art—which comes courtesy of Matt Frith—quite literally sets the scene for the game, and there were countless “this frame a painting” moments in The Drifter. I wish I could be as complimentary of the voice acting overall, although I chalk up my distaste to personal hang-ups about ockerisms and the Aussie accent “in film”. I do think the writing is especially sharp, particularly the lines told through Mick’s inner monologue; however, hearing it read aloud in the most “bloody streuth” accent ever is mildly off-putting.

I knew from early previews and seeing it at PAX from time to time that The Drifter would resonate with my interests. I didn’t quite expect just how much I’d adore it after rolling credits, however, as it joins a shortlist for the year’s best offerings. It’s hard not to respect how Powerhoof succeeded in modernising one of gaming’s most enduring genres in a profound way that makes for a more fun experience, while empowering the narrative and cinematic pedigree of the game itself.