I’ve never been one to deep-dive into stats, or to love trawling menus. I always preferred my roleplaying games with that westernised stank, which pretty much saw all of the traditional tropes stripped back in favour of a more action-centric flavour. So while I would fool myself into thinking I’m a dungeon-trawling grand master because I laboured through Bioware’s Dragon Age, little did I know what awaited out there.

There’s a lot of circular inspiration that goes on here, so let’s see if we can make sense of it all. Monte Cook, visionary Dungeons & Dragons designer, was inspired by David Cook’s Planescape campaign which led to the birthing of his own fantasy setting, Numenera. The developer folks at InXile, in turn, were inspired by Planescape: Torment, the game adaptation for David Cook’s campaign, and based their own adaptation of Monte Cook’s Numenera on it, making Tides of Numenera both a thematic and spiritual successor to Planescape: Torment.

Phew, that’s a convoluted tale.

Nonetheless, Torment: Tides of Numenera very much abides by the traditional tabletop ruleset. It prioritises the drive of its engrossing story and interacting with the world and characters in it over combat and the finicky organisation of inventory. The narrative, including the delivery of it, blow most of its contemporaries out of the water. Bethesda, masters of the ‘modern RPG’, only wish they had this capacity for storytelling.

Nonetheless, Torment: Tides of Numenera very much abides by the traditional tabletop ruleset. It prioritises the drive of its engrossing story and interacting with the world and characters in it over combat and the finicky organisation of inventory. The narrative, including the delivery of it, blow most of its contemporaries out of the water. Bethesda, masters of the ‘modern RPG’, only wish they had this capacity for storytelling.

Tides of Numenera places you in the shoes of The Last Castoff, the final clone of The Changing God, an immortal being capable of transferring his consciousness from vessel to vessel. Little does he know that when a vessel is emptied, a new consciousness awakens within it to fill the void, creating a ‘castoff’. The reckless abandon that The Changing God operates with has attracted a devouring entity called Sorrow, who aims to end The Changing God and his clones, in an effort to restore the now unbalanced tides. The story, of which you can’t experience it all in a solitary playthrough, is so well-written at times that it would put a great number of fantasy authors to shame. Though, on the flipside, it isn’t without its consistencies, on occasion slumping into a bad fan-fiction quality twenty minutes that could often sever the immersion entirely.

There are also instances that sometimes screamed to me that the ambitions of the writing weren’t quite matched by the game design, as passable as they both are in isolation. In the very early game, after you’re revived near the ‘resonance chamber’, you wander less than a handful of screens across to the next town where it turns out it’s a mythical machine, only heard of in old stories. In reality, if these townsfolk wandered 100m to their left they’d happen upon it with almost no effort at all. This was infrequent, but I could help but laugh when it did happen.

There are also instances that sometimes screamed to me that the ambitions of the writing weren’t quite matched by the game design, as passable as they both are in isolation. In the very early game, after you’re revived near the ‘resonance chamber’, you wander less than a handful of screens across to the next town where it turns out it’s a mythical machine, only heard of in old stories. In reality, if these townsfolk wandered 100m to their left they’d happen upon it with almost no effort at all. This was infrequent, but I could help but laugh when it did happen.

The game has a karmic alignment system built-in different to most other games of this ilk. Instead of being defined by morality and intention, the tides are moved and worked through action. The five colour-coded tides all represent higher concepts. For example, those attuned to the Gold tide value philanthropy and empathy and aim to help others, no matter the toll. It’s an interesting system that forces you to take great care when in dialogue, especially if you hope for your lasting legacy to be a positive one. It’s one of the main reasons why taking the pacifist route in Torment is, quite honestly, the most enjoyable path. The other main reason being that, well, the fighting simply isn’t that fun. (It doesn’t help that the only hard crash I experienced came at the end of an exhausting battle.)

I made it a handful of hours into the main game without being forced into a conflict, excluding the one in the game’s tutorial. Now, I’m a persuasion player at heart, hoping to talk my way out of most situations, so when I’m thrust into a fray, it’s not likely ever going to end well for me. Each combat set-piece is a turn-based ballet where the artistry, to be blunt, is just lost on me. A mix of ineptitude and lack of interest in being a fighter saw me scraping through the infrequent ‘crisis events’ in Torment. I’d die often, but unlike other games in this genre, death isn’t the end. In Torment, death is as much a consequence-laden choice as a strongly-worded rebuttal is. In the traditional sense, The Last Castoff cannot die, he is constantly thrust back into the world to deal with the enormity of his failures.

If I were playing a game like Mass Effect and I lost a party member due to my destructive hubris, I admit that I’d be quick to load, try and try again until I found an outcome that suited my idea of some satisfactory narrative advancement. In Torment, for the betterment of the story being told, I abandoned this habit. I didn’t cry when the milk spilt or went bad altogether, I pressed on and dealt with it. Torment, in its first few hours, forced that change in me, so compelling is its world-building and lore.

I did find the overall movement in Tides of Numenera somewhat cumbersome as I would constantly get caught on edges of the game’s 2.5D isometric environments. The Last Castoff has the turning circle of a shopping trolley, but fortunately, time spent wandering won’t come close to the time spent reading. Each area has a bevy of people to talk to, each one managing to come across as significant, not to mention the titular ‘numenera’ scattered throughout the Ninth World setting. ‘Numenera’ is the name given to the strange and wondrous devices left over from bygone civilisations. Some of these oddities are simply to gaze upon, whereas others hold a use, such as the one-use Cyphers you’re able to collect. Hold onto too many at once, however, and you’ll be saddled with a sickly health state.

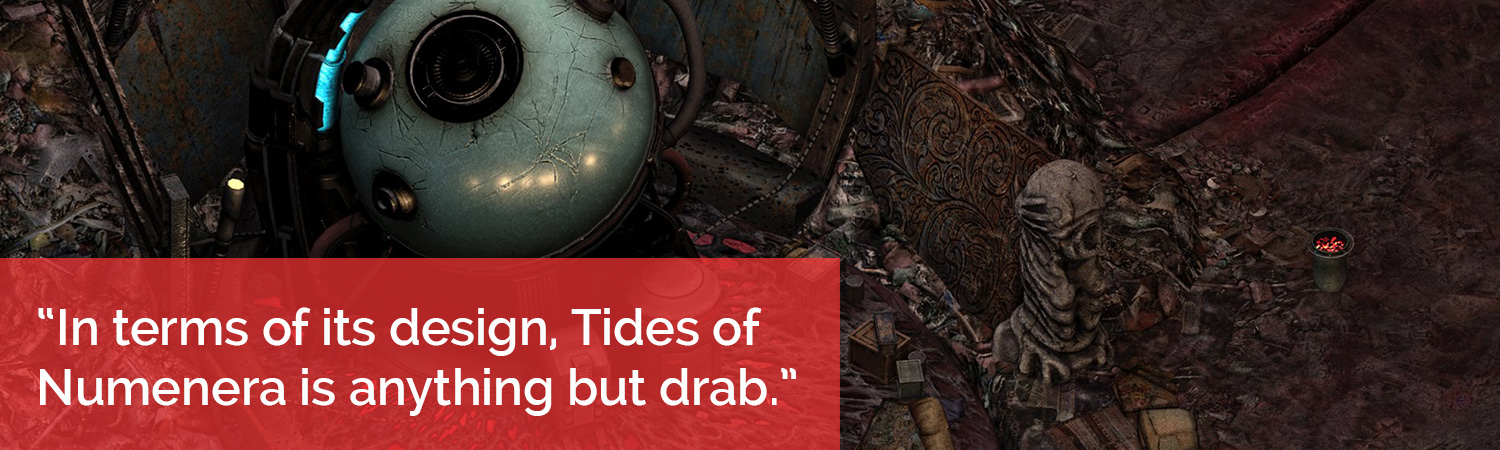

In terms of its design, Tides of Numenera is anything but drab. Whether you stop and stare at the indigo starburst lurking in the void beneath you as you explore the deep, labyrinthian recesses of your mind, or you pause to ponder the world at large, it’s clear Torment is not a dull game. It isn’t what I’d call a pretty game, either. Blocky models, sub-par animation and some truly heinous menus don’t mar the experience at large, but it certainly doesn’t help. Plus, as occupied as they seem, none of the pre-rendered areas are all that big and yet the load times can be quite lengthy. This is unfortunate, as most of the doors in these areas are pretty close together. Resources were likely spread thin, given the scope of the game, and I’d say, given the result, the right choices were made. In a game like Tides of Numenera, plot is paramount, so these flaws are certainly something to forgive. In a game where you’re bound to read for hours upon hours, voice acting isn’t featured too prominently. It’s so infrequent, in fact, that I question why they bothered at all. Though, when a character is blessed with a working set of vocal cords, you can be that it’ll be both out of the blue and hilariously bad.

CONCLUSION

I seriously can’t speak highly enough of the world this game presents. I found value in every corner I poked my nose into. Its people, its creatures and its oddball take on what society could be like in a billion years places Torment among the best of its kind. Torment’s world has a lasting appeal. Much like a good book you’ve closed for the last time, you’re left with a sort of bitter understanding that you’ll never experience it for the first time again. So, you settle for seconds.

Unfortunately, some presentation issues including voice acting and being a little graphical unimpressive stops this game from being a true masterpiece.

The Xbox One version of this game was played for the purpose of this review. You can read our review policy HERE.