The symbolism of the cocoon isn’t lost on me, given Cocoon is Geometric Interactive’s debut title and, therefore, it serves as something of a fresh start for Jeppe Carlsen, who served as lead gameplay designer on games like Limbo and Inside. In terms of craft, it feels like a natural progression on the insanely clever puzzle design he’s displayed throughout his career so far. If anything, Carlsen is so in tune with gamer psychology and how they approach problem-solving inside of the medium that Cocoon practically reads the player like a book.

As one who found himself arrested by Inside especially, I can’t help but once again gush over the one facet of development where Jeppe Carlsen continues to prove himself a master. With award-decorated titles already on his résumé, Carlsen would nearly be a shoo-in for the Game Design Mt. Rushmore, and it feels as though Cocoon is the culmination of the quasi-trilogy that includes his prized works from Playdead. So different and yet so alike, all at once.

There are a few through lines when it comes to the philosophies of both Limbo and Cocoon’s puzzles, despite them being very different games. Cocoon might have begun its life as a riff on The Legend of Zelda, with its world feeling like a honeycomb of dungeons, but it maintains the older game’s same approach of simply sending the player out into the world. Cocoon’s trial and error revolves less around a bleak, monochrome cycle of death, but it refreshingly challenges the mind in a similar way. No one solution is difficult to execute, but the solution itself requires quite a bit of lateral thinking.

Although Cocoon plunges you into its enigmatic world without a shred of context or explanation, the importance of orbs, and their intrinsic link to the gameplay loop, becomes immediately evident. There are plain spheres you carry on your back like a pack mule which aid in opening chasmic entrances, however it’s the ones you absorb from the dissipation of each level’s guardian that bestows a power that continually subverts what you expect from the game.

The first you collect acts as a pathfinder, revealing once-hidden tracks to the player and further peeling back the petals to these quaint, rosebud-like worlds. The second grants the ability to transform other, organic parts of the world to create solid pillars to traverse across. Along with granting power to the player, these orbs are gateways to other worlds and therein lies the magic of Cocoon. The worlds you’ll frequent are more layered than an ogre’s onion, and once it locks into a high gear and the puzzles you solve bear effect in the layer above or beneath, it’s a special thing to behold.

There’s so much more satisfaction in solving a Jeppe Carlsen head-scratcher than can be found in most games. There are notes of catharsis that provide the kind of emotional release that just isn’t commonplace in games. I happened across all of the solutions to Cocoon’s first three so-called dungeons so naturally, which speaks to how intuitive the design really is and how Carlsen can get into the minds of those tasked with unravelling his mysteries and remain a couple of steps ahead at all times.

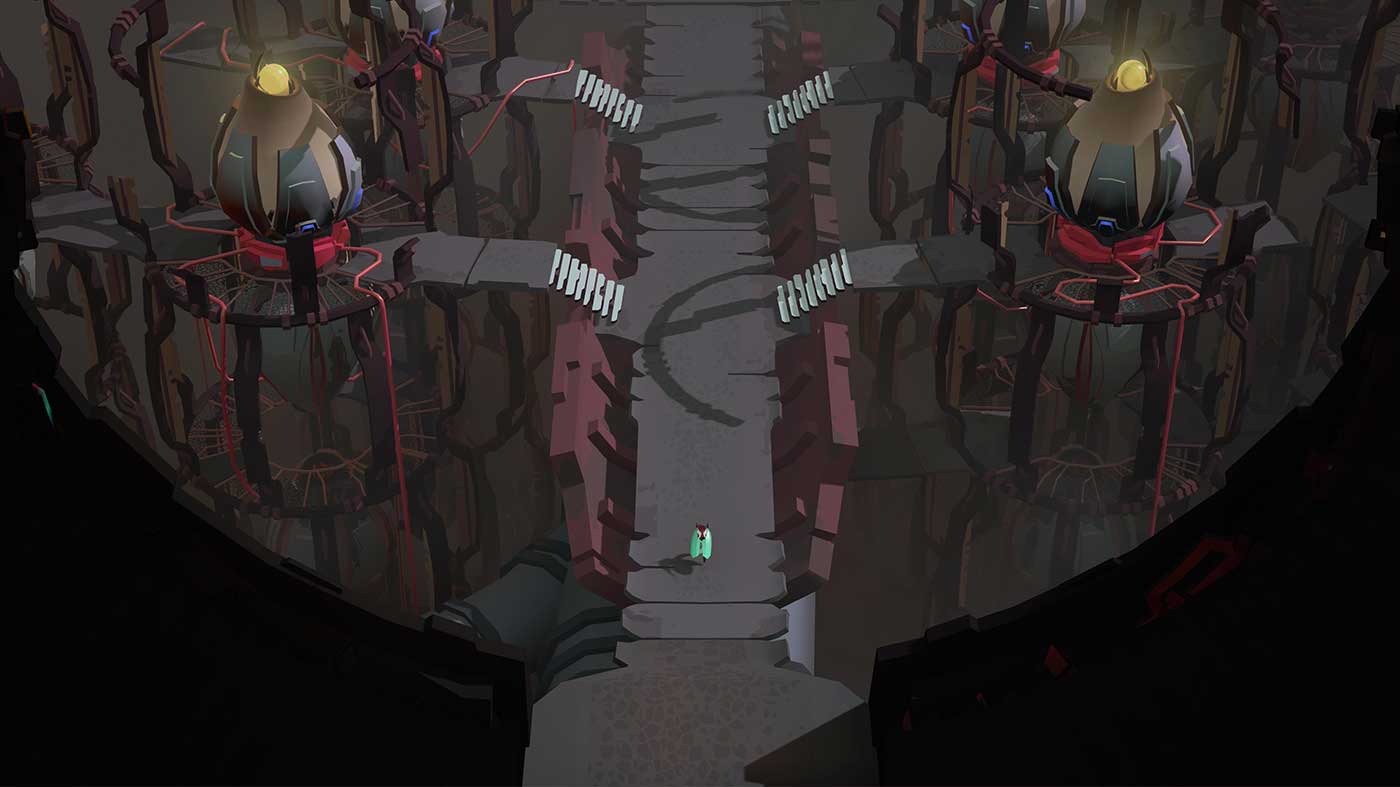

Unlike Limbo, which is very much tailored around the grim cycle of death, Cocoon doesn’t feature a ‘death state’ at all. As previously mentioned, the game frames its monumental encounters as a struggle for control against those safeguarding the many spherical worlds in Cocoon. They do require pattern-recognition without being too punishing, and failure doesn’t condemn players to repeat big sections of the game, rather they’re turfed to the layer above by the guardian and can dive back in almost instantly to restart the challenge from the first wave. For a game that doesn’t include any traditional combat, the way it incorporates learned mechanics into these tussles is grand.

By not delivering a clear-cut narrative, Cocoon maintains an allure throughout. Without a morsel of dialogue, it delivers a narrative shouldered by world-building and lore baked into the environment. Much like Inside, which I took pleasure in unpacking in time, I suspect Cocoon’s message is either that of unmistakable outer transformation, private inner dealings, or even a combination of both—however, I’ll leave it to those smarter than me to unravel the game’s secrets. Literally everything this game does or says is visual, and it’s dynamite in terms of technical spectacle and art direction. The orbs you inhabit are reflective of their outer hue and offer up a beautiful, colourful variety of space to explore, and the game’s particle effects are mesmerising.

All of that pales in comparison to the jaw-dropping effect of escaping into an orb to search for and unseat its champion, once you stir it from its likely eons-long slumber. It’s something you’ll do a lot of and it truly never got old, it’s such a stunning flourish that sells the magnitude of these worlds that can feed into each other like stacking dolls while functionally serving as a seamless, and near instant, load that really seems like a magic trick at times.

From both a design and technical standpoint, there’s a lot of mastery on display in Cocoon. The sheer skill to present a veritable blank canvas of a world and put tools in players hands knowing full well they’ll weave through the intuitive tasks like a knife through butter is sign of a confident design philosophy that, for Carlsen in particular, continues to hit pay dirt.