The most interesting and well-rounded characters in fiction (and non-fiction) are never perfect. Be they a protagonist, an antagonist or a bit player in the narrative, imperfections make a character believable and human (where applicable, of course). This notion rings true for all forms of media, including video games. But, while some of gaming’s most memorable written characters certainly exhibit the kinds of foibles that make them relatable, it’s the unwritten ones that need more help. By which I mean the kind of characters that we see in RPGs and adventures where the player is given free reign to create and develop a character of their own. The kinds of games where a starving, naked scrub slowly but surely transforms into a nigh-invincible hero, molded in the image that the player has designed for them.

These kinds of characters, and their stores, are just fine. But there’s a better way, and I didn’t know it until I played The Outer Worlds.

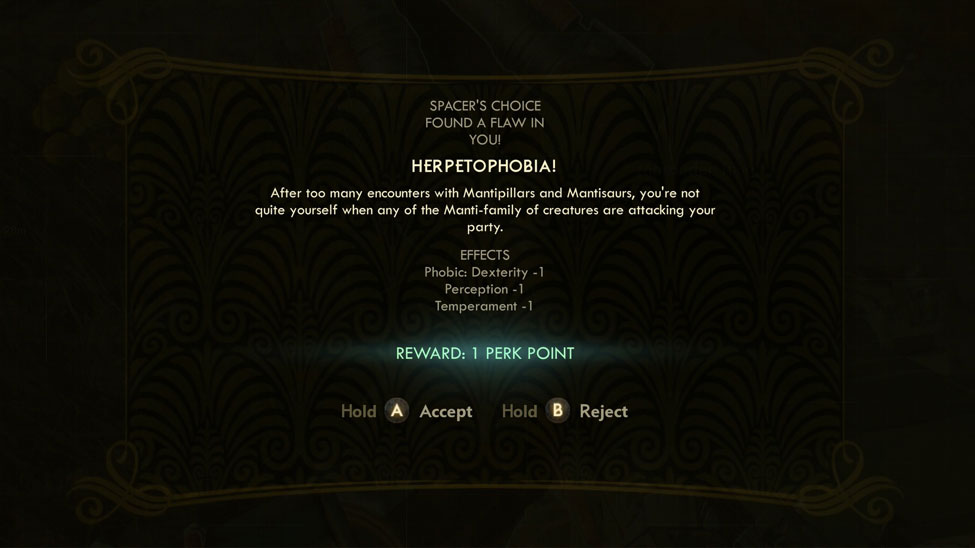

There’s a kind of ‘penny drop’ moment when you’re playing The Outer Worlds, the new sci-fi first-person RPG from Fallout New Vegas and Pillars of Eternity developer Obsidian. That moment is precisely the first time the game offers you a ‘Flaw’. It might be after a tough fight with a certain kind of enemy, it might be from spending a long time in the dark. Hell, it might just be from falling off a ton of stuff. Whatever the circumstance, at some point the game will present you with a choice; carry on as you were or take on a debilitating character flaw relating to the situation in exchange for an extra perk point to spend however you desire.

These Flaws typically add some kind of extra penalty to your character when faced with the relative situations. So, if you took on a fear of heights, your character’s fall damage might increase, or a fear of Marauders could mean that your character becomes less effective in encounters with them. Obsidian are yet to reveal all of the available Flaws, but they seem to come in all kinds of flavours from combat, to environmental and even social — meaning that their effects will be felt in all kinds of ways. There’s nothing more entertaining in a tabletop RPG than someone having a character with a seriously inhibiting trait that consistently gets them into trouble, and The Outer Worlds comes as close to that as I’ve experienced in a video game. That penny drop moment? It’s the moment that you think to yourself, “Why hasn’t this been done this way before?”.

Of course, the idea of an imperfect hero isn’t a new thing in RPGs by any stretch. Plenty of progression systems in games present their players with stat-based conundrums and quandaries about whether to take this buff over the other. Without some built-in measure of deficiency every game would end with the player transcending God and storming the gates of heaven. Even the Fallout series, including New Vegas, has dabbled with the idea of character traits that boost one area of development while compromising another. The difference with The Outer Worlds is that, as with almost every other facet of the game, Flaws arrive as a direct result of your actions, and have a tangible and permanent effect on your actions in the future.

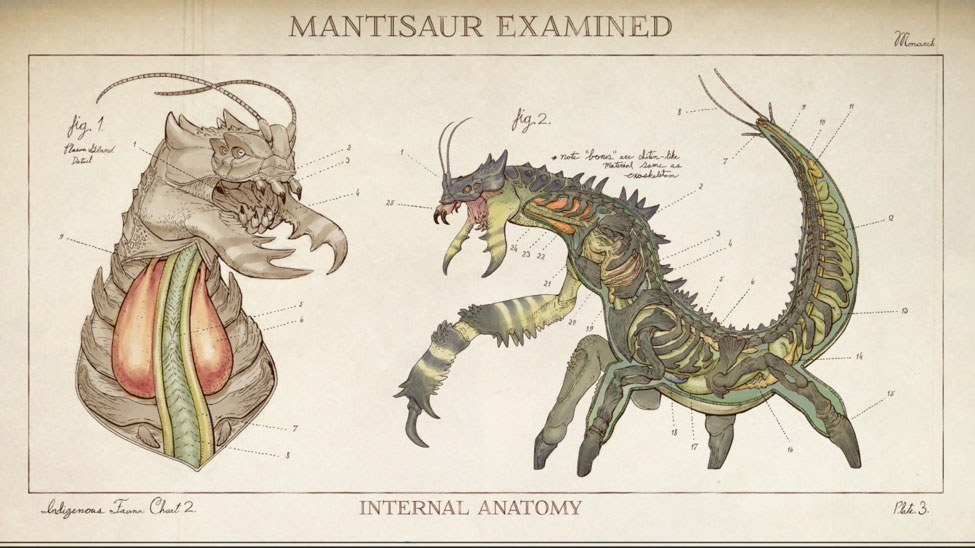

During my short hands-on time with the game, I only managed to earn myself one flaw — Herpetophobia. I got that one for having a few too many run-ins with the Mantisaur enemies, giant insectoid monstrosities that, honestly, I would be shit-scared of in real life as well. The Flaw meant that any time my party had a run in with these creatures, I’d take a hit to my Dexterity, Perception and Temperament during the encounter. “That’s cool”, I thought to myself. “I’ll just avoid them where I can”. So I took the Flaw, and my shiny new Perk Point and continued on my current quest to help my companion Nyoka find the grave of one of her fallen friends. Turns out, dear reader — that grave was smack-bang in the middle of a cave full of Mantisaurs.

Great job, me. That hurt, but it was also another indicator of just how effective such a simple idea can be. Normally, RPG systems love to live in the background; every character’s stats and skills determining, invisible to the player, how their encounters play out. In The Outer Worlds, your Flaws feel tangible because they have a visible relationship with what you’ve done and what you’re doing. After taking the Herpetophobia Flaw, I felt my character’s fear of Mantisaurs as soon as I was faced with them. I knew that they were going to be trouble, and for every hit my character took to their abilities in that fight I was taking one to my own confidence. Role playing games are at their best when players are doing just that — role playing, and Flaws are a genius way to make that happen.

In my brief interview with game’s lead designer, Charles Staples, I asked him how many Flaws a single character could take on. The answer is three, four or five, depending on the selected difficulty level. That means that at the end of the day, despite the unique twist on RPG progression, The Outer Worlds is still a typical video game power fantasy, because my character in the game will never be as flawed as I am in real life.